What began as a normal labor union strike has morphed into what could be Colombia’s biggest anti-government protest in recent memory. Here’s how that happened.

Much has to do with President Ivan Duque and his cabinet’s inability to attend both specific demands of interest groups and and general discontent.

Additionally, Colombia’s clumsy ruling party, business associations and finance minister have created a climate of resistance.

The leftist opposition has taken advantage of this while center right parties are hoping to gain political leverage from Duque’s political self-destruction.

How it all began: the tax reform debacle

Alberto Carrasquilla celebrating his illegal tax reform in December last year. (Image: Finance Ministry)

The national strike was formally announced on October 4, which happened largely unnoticed, mainly because the country’s pro-government media ignored it.

By then tensions were already high, but simply ignored.

The first seeds of dissent were sown by controversial Finance Minister Alberto Carrasquilla, who in October last year presented a tax reform that sought tax cuts for corporations and a lower threshold for the middle class.

Ahead of his election in June 2018, Duque had promised tax cuts but did not mention this would be exclusively for corporations and that the average Colombian was expected to increase contributions.

While some of the most controversial tax reforms were removed from the so-called “budget finance plan,” Colombia’s voters felt betrayed and Duque’s approval rating plummeted to 29%.

Carrasquilla had said the corporate tax cuts would create jobs, but of course they didn’t. In fact, due to unrelated circumstances, unemployment shot up.

Colombia’s finance minister doesn’t understand unemployment or know how to fix it

Security policy fails

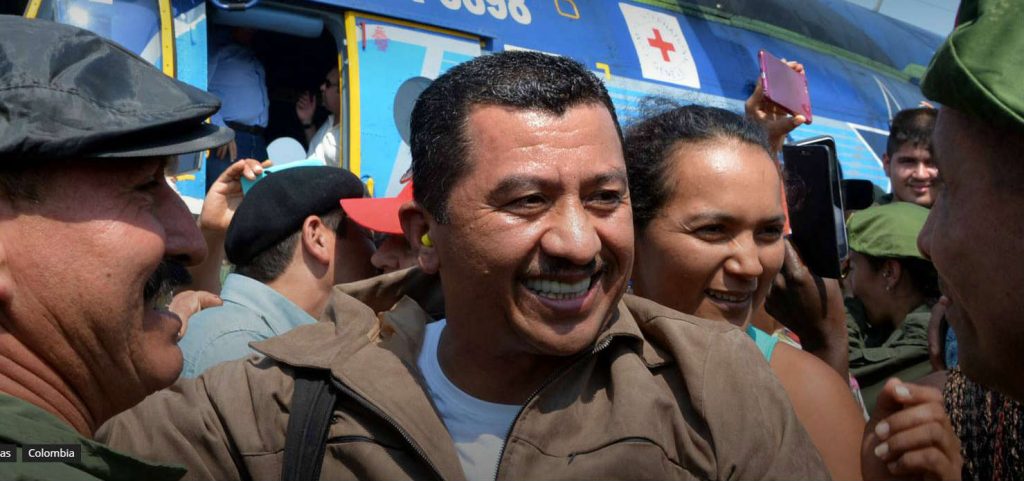

FARC dissident leader “Gentil Duarte” (Image: FARC)

Duque’s far-right party, whose allies in politics, business and the media are neck-deep in war crime allegations, has opposed peace with the FARC since before talks even began in 2012.

Even before taking office in August 2018, the Democratic Center stigmatized any supporter of the 2016 peace deal as a guerrilla sympathizer.

This aggravated the mass killings of victims and ethnic minorities who were reclaiming stolen land, community leaders implementing the peace deal’s counternarcotics program and human rights defenders defending peace.

After taking office, the government formulated a security policy that ignored the peace process and the security challenges that had arisen as a consequence of the FARC’s demobilization.

At the same time, the party sought to appease the erratic US President Donald Trump and pursued an aggressive counternarcotics policy in violation of the 2016 peace deal and against the advice of experts.

Why Colombia’s estimated cocaine exports went up 13% in 2018

The corruption scandals

General Nicasio Martinez (Image: Colombian military)

In December last year, the president replaced the military command with officials close to his political patron, former President Alvaro Uribe.

These military commanders, however, were not just of the most radical wing within the security forces, many were accused of crimes against humanity and corruption.

This initially was revealed by the New York Times in February, but followed up by a series of revelations of corruption and the apparent return of the killing of civilians who were presented as guerrillas killed in combat.

While Duque and his Defense minister Guillermo Botero were trying to defend their military allies, at least six top generals were sacked, some for their intimate ties with drug trafficking organizations.

Colombia’s 4th Brigade: an army unit or an organized crime group?

#TheyAreKillingUs

A woman in Medellin wears a sign saying “Maria del Pilar Hurtado, we will not forget your name.”

Meanwhile, the mass killings of social leaders isolated Duque’s minority coalition in Congress and led to increased resistance against the return to violence.

This came to a climax in March when indigenous groups organized a protest in opposition to the increased violence by rearming FARC guerrillas, ELN rebels and paramilitary groups.

The native Colombians and other social leaders received massive support in March when tens of thousands took to the streets to demand an end to the violence.

Duque, however, refused to talk to the native Colombians. Instead, the protests were violently struck down and the indigenous retreated in April to rethink their strategy to force the government to comply with the peace deal.

President expelled from march in support of Colombia’s human rights defenders

FARC dissidents rearm

“Ivan Marquez” (Image: YouTube)

Citing the government’s consistent failures to implement the peace deal and attempts to sabotage the process, the FARC’s former peace negotiator, “Ivan Marquez,” announced he and some 15 other commanders were rearming in August.

Duque responded by declaring war against them,but found himself isolated.

The peace movement urged Duque to implement the peace deal and pushed the leftist opposition and the center-right voting bloc together. Support for both Marquez’ and Duque’s call for a return to war were widely rejected.

The government responded by conjuring up a conspiracy theory that ties Nicolas Maduro to the ELN and the FARC dissidents, but the president found himself humiliated in front of the international community when presenting fabricated evidence before the United Nations General Assembly.

Colombia admits fabricating at least four pieces of evidence against Venezuela

The students rise up

Student protests in Barranquilla last month. (Image: Twitter)

Corruption at a Bogota university triggered student protests in late September that were violently struck down by the police.

This led to solidarity protests that were met by similar violence.

Student organizations joined and organized weekly marches throughout Colombia. Furthermore, they announced they would hold protests on November 21, the day of the unions’ national strike.

Duque struggling to respond to Colombia’s swelling student protests

The Uribe trial and the elections

On September 3, the Supreme Court began hearing witnesses in the trial against Duque’s political patron, who is suspected of having used fraud and bribery to conceal his family’s alleged criminal past.

From day one, testimonies and evidence emerged about the Uribe crime family’s past. By October 8, when the former President had his first day in court, his reputation had been destroyed.

In local elections on October 27, the ruling party received an electoral beating and lost control even in Medellin, the stomping ground of the “uribistas.”

This caused a major crisis in the CD, because many of Uribe’s allies are implicated in crimes related to the fraud and bribery charges.

Duque brutally punished in Colombia’s local elections

The genocide

(Image: Senator Feliciano Valencia)

Following Duque’s refusal to talk with native Colombians in April, the violence targeting the indigenous accelerated, particularly in southwestern Colombia.

The president sent Interior Minister Nancy Patricia Gutierrez to the southwestern Cauca province, but the notoriously inept minister was unable to hold meaningful conversations.

The national indigenous organization declared a humanitarian emergency, but got no significant response from Bogota.

After the massacre of an indigenous governor, the ONIC announced last month that all indigenous organizations would take part in Thursday’s strike.

Other ethnic minorities and dozens of social organizations joined.

Indigenous governor, four guards massacred in southwest Colombia

The arrogance of the CD and the business leaders

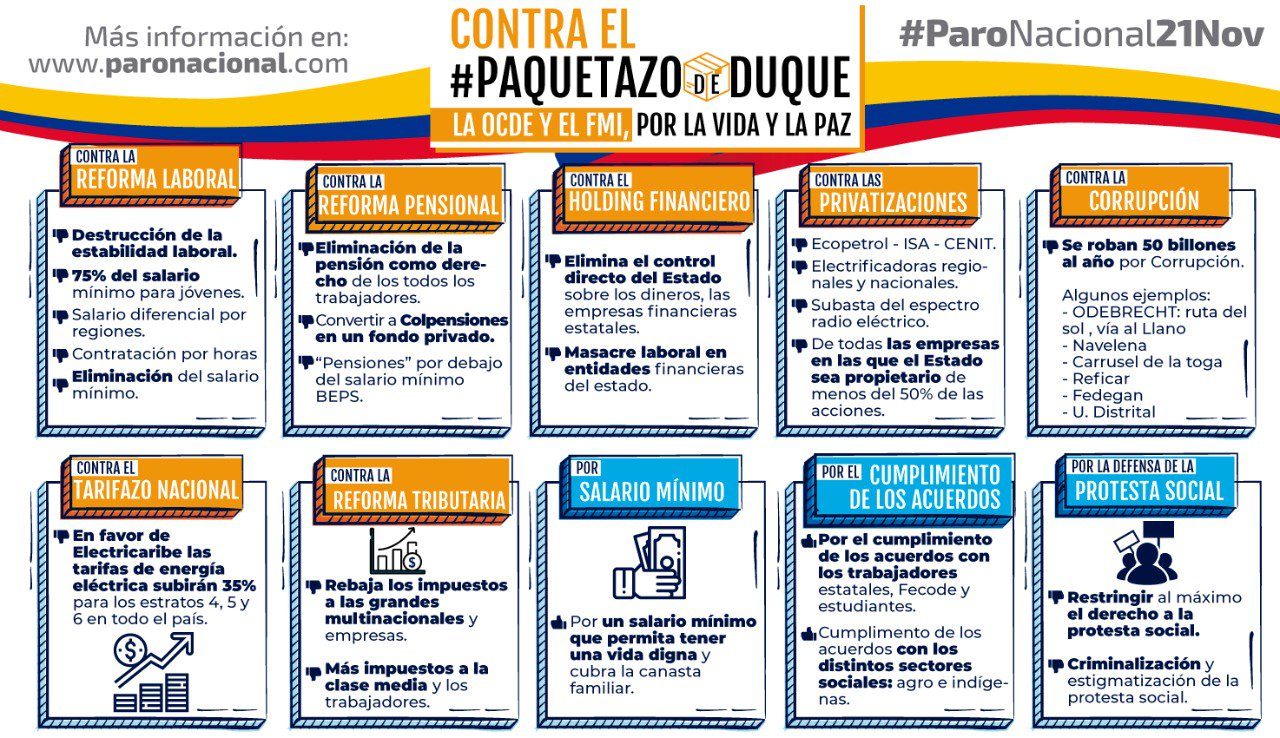

To make things worse, business leaders close to Duque began proposing all kinds of controversial measures like lowering the minimum wage for young people and paying people per hour.

To make things worse, business leaders close to Duque began proposing all kinds of controversial measures like lowering the minimum wage for young people and paying people per hour.

The CD additionally proposed to increase the pension age.

None of these ideas came from the government, but became part of what the mushrooming protest movement called “Duque’s great package.”

The government tried to distance itself from these proposals, but had lost all credibility by then. Duque’s disapproval rating rose to 69%.

Approval rating of Colombia’s president hits record low

The final drop of blood

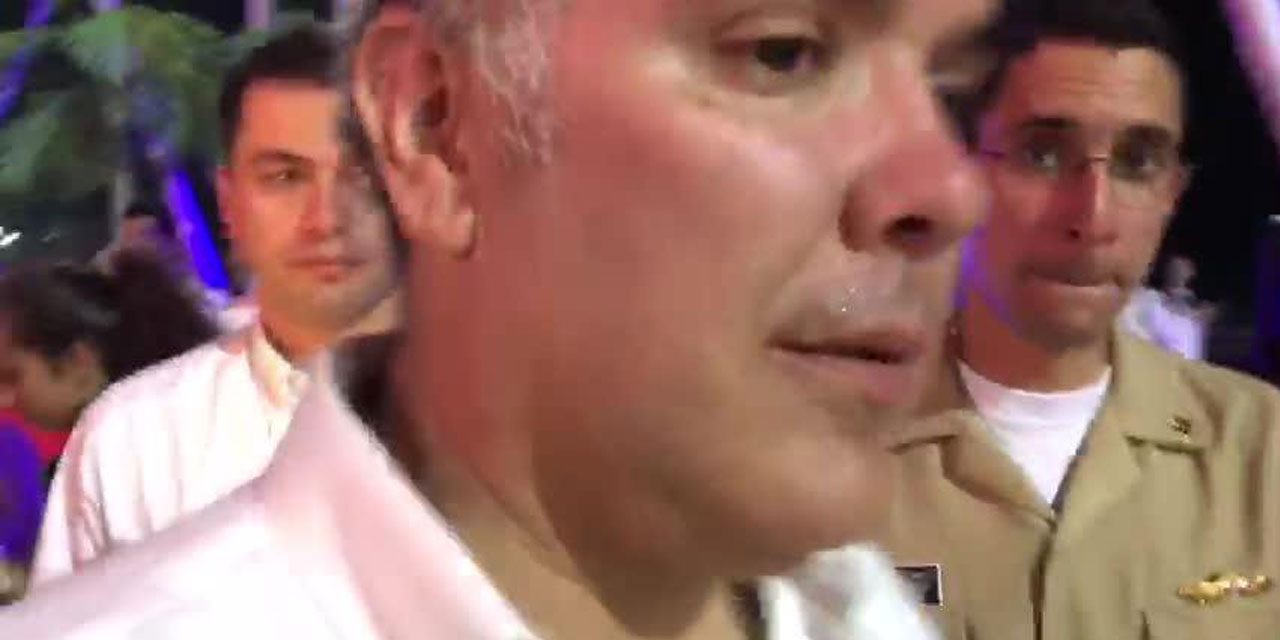

President Ivan Duque (Image: Twitter)

When the prosecution confirmed earlier this month that Duque had authorized the bombing of at least eight underage victims of forced recruitment in response to Marquez’ rearmament, everything went wrong for real.

The defense minister was forced to resign and Duque appeared to be having a mental breakdown, desperately trying to pretend not knowing about the bombing of the FARC dissident camp he had boasted about in August.

Did Colombia’s president know he was authorizing the bombing of children?

The rejection was almost unanimous; all political parties but Duque’s, football fan clubs and even Miss Colombia called to march against the president.

The national protests were called before unrest in Ecuador and Chile almost brought Duque’s regional allies to their knees. But these protests have “woken up” Colombia, according to the protest.

The president has also woken up, but entered an apparent state of catatonia. Colombia’s youngest and least experienced president of the past 100 years is facing protests none of his patrons have ever dealt with.