Colombia’s outgoing President Ivan Duque has divided media between allies and enemies, which contributed to polarization in the country and limited citizens’ access to information, according to press freedom foundation FLIP.

Duque ended his May interview with BBC’s program HARDtalk, claiming its name “should be HARDlies” after host Stephen Sackur debunked multiple of the president’s false claims with facts.

Duque’s growing aggression against the BBC host and his final statement was typical the outgoing president’s relations to critical members of the press that refused to become Duque’s propaganda tools.

In the interview, the president falsely claimed that Colombia’s homicide statistics were the lowest in history while they were the highest since 2015, according to the Defense Ministry.

Despite Sackur’s pushback and the facts, Duque insisted that his claim was accurate and — to the amusement of many — ultimately claimed that the BBC was spreading lies.

The interview was telling how the president over the past four years has made a clear distinction between “allied” media that allowed Duque to make all kinds of false claims and “enemy” media that were shunned for exposing the government’s barrage of lies, half truths and utter nonsense.

Rebuilding Colombia Reports after 4 years of repression

Building the propaganda machine

In an attempt to strengthen his communication, the president expanded his propaganda team from 15 people to 54, and invested more than $10.3 million (COP 45 billion) to dominate the public discourse with his fabricated narrative.

The team monitored media and journalists in order to define which were deemed positive about the Duque regime and which were “negative” and had to be countered, particularly during one of the government’s many crises.

Meanwhile, violence against the press intensified. At the end of Duque’s four years, five journalists were assassinated and 750 journalists were threatened with censorship.

Duque reverting freedom of the press to Colombia’s ‘darkest days’

“Allies” and “enemies”

After taking office in 2018, the president briefly tried to maintain cordial relations with the press, but this quickly ended and journalists became either “allies” or “enemies,” which helped create a climate of polarization, according to the FLIP.

“We know that there are media that don’t like us, that there were media that supported “Yes” [during the 2016 campaign that sought the public approval of a peace deal with now-defunct guerrilla group FARC and are friends of [former President Juan Manuel Santos,” one of Duque’s advisers told the president, according to an anonymous former adviser, who added that “that sentence left me worried.”

“You can’t being a government with a predisposition for the attack,” the former adviser told FLIP and let to the government’s believe that some media were part of the political opposition.

The beginning of the censorship

Three months after taking office, Duque’s public television chief Juan Pablo Bieri censured a television program whose host was too critical about the government’s “ICT modernization Law,” which gave the administration almost absolute control over the content on public TV and the allocation of radio frequencies.

Bieri was sacked and immediately hired as one of the president’s communications advisers after which the official help organize a WhatsApp groups with loyalists of Duque’s far-right Democratic Center party that sought to silence criticism by media and political opponents of the government.

‘Democratic character of Colombia’s state put to the test’: press freedom foundation

Profiling social media critics, spying on journalists

After the president’s popularity collapsed in 2019 and anti-government protests were being organized, the president hired a firm to “construct a narrative that would make good Colombians disapprove the motivations of those who marched” against the administration.

The President’s Office also sought to label influential citizens on social media as “positive,” “negative,” and “neutral.”

Weekly Semana additionally published evidence indicating that the National Army had been spying on more than 70 journalists and other public figures, which exposed that the army was managing a list of “opposition” politicians.

Colombia’s army spied on court, politicians and journalists: report

Public uproar forced a change in the president’s communication team and the appointment of far-right pundit Hassan Nassar as Duque’s top communications adviser.

Nassar quickly showed that that any journalist asking critical questions would be accuse of having ties to Santos. Media subsequently avoided the president’s communications chief, who became the laughing stock of internet trolls.

Press freedom in Colombia deteriorated in 2019 amid persistent aggression and self-censorship

Politicized public service announcements

The coronavirus pandemic that broke out in Colombia in March 2020 triggered Duque to host a daily propaganda program that was broadcast on corporate television networks deemed loyal to the government.

Until March that year, the president gave 272 interviews to these corporate media and made 327 public statements that were loyally broadcast by them.

The strategy sought to “exercise a control over the information that was going round,” according to political news website La Silla Vacia.

The president’s daily “Prevention and Action” program that was initially introduced to inform people on the progress of the coronavirus turned out to be a disaster for radio news programs that broadcast in the morning, but had to wait for answers until the evening.

Additionally, independent media deemed hostile by the president’s inner circle were shunned, which ended up isolating the president ahead of April 2021 when social organizations began organizing a new National Strike that sought to revive the massive 2019 protests.

The tragedy of Hassan Nassar, Colombia’s propaganda chief

Criminalizing protests

The president’s daily broadcast gradually reduced information on the coronavirus and increasingly became a propaganda program that highlighted Duque’s self-proclaimed successes and broadcast claims that sought to discredit and criminalize the impending protests.

A week after the 2021 National Strike erupted the program was taken off the air and the corporate television stations loyal to the government began criminalizing the protests based on “intelligence” provided by the security forces.

The FLIP said that press conferences were held exclusively for corporate media that replicated the government’s talking point.

Duque additionally extended the maximum term for open information requests to two years, making it virtually impossible for news media to inform their audiences on information that had not been vetted by the president’s propaganda team.

On May 21, 2021, as Duque came under international pressure over his violent crackdown of the largely peaceful protests, the president published to publish fake interviews in English to manipulate international opinion and blame opposition leader Gustavo Petro of the unrest.

The auto-interviews further distanced the president from citizens as most didn’t understand a work Duque was saying.

Fact-checking website ColombiaCheck later published that 46 of the 96 claims made by Duque in these interviews with himself were “questionable,” 19 were false 16 were true, but deceitful and only 15 were simply true.

On May 7 last year, the security forces and government website simulated a cyber attack on its social media platforms and some websites in order to justify the “cyber patrol” of 1.7 million citizens’ social media accounts, of which some were branded as “fake news” because they published content that had not been approved by the military and the National Police.

Colombia Reports’ Facebook page taken down in apparent cyber war

Bailouts and trudgens

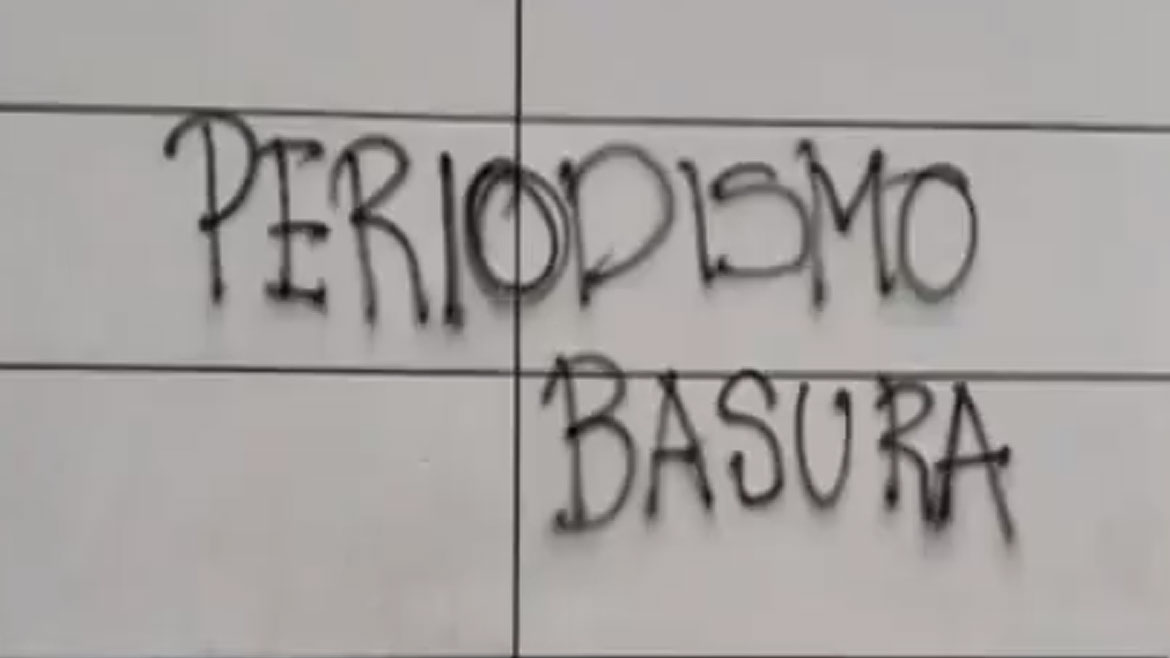

Tensions between the corporate media that were given interviews by the president and replicating government lies increased tensions with anti-government protesters that one multiple occasions attacked these media’s offices or exposed their reporters to aggression.

In order to help these media, the government offered bailouts that were withdrawn in September because of the government’s attempt to further control these media’s news programming.

Hundreds of journalists reporting on the protests, and particularly the mass violation of human rights that sought to quell them, were injured, mainly by police.

By the end of Duque’s term, Duque had burned many of the bridges with the press and was unable to respond to particularly harsh press reports about the human rights violations committed by his administration and the corruption scandals that had emerged.