Colombia’s peace process with Marxist FARC rebels is by far the most significant step towards peace since the demobilization of paramilitary organization AUC between 2003 and 2006.

The process began on December 1, 2016 after more than five years of negotiations to end the armed conflict that began in 1964 and cost the lives of more than 265,000 Colombians, left another 45,000 missing and 7 million displaced.

Peace talks with FARC | Fact sheet

The process seeks to effectively disarm the FARC and convert them into a legal political movement. Meanwhile, the state will try to assume territorial control over territories long under control by the guerrillas.

A transitional justice system is put in place to prosecute the tens of thousands of human rights violations committed by both the state and the guerrillas.

The process also seeks to curb some of the causes of the conflict, rural inequality and the political exclusion of the left.

Additionally, the process seeks to curb drug trafficking, the illegal industry that has fueled the violence since the early 1980s.

Therefore, the process consists of a major land reform, major rural reforms, a crop substitution program for coca farmers and increased efforts to cut ties between the country’s political and economic elites and paramilitary successor groups.

Skip to

Top – The war – The talks – The deal – Disarming FARC – Reforms – Victims, truth and justice – Timeline – Resources

The war

The conflict between the FARC and the Colombian government began in 1964, but political violence closely related to the current conflict began decades earlier.

Colombia has never had much of a stable democracy. In its more than 200 years of existence, the former Spanish colony has had more than a dozen constitutions.

These radical constitutional changes were partly due to a partisan division between Conservatives and Liberals, an ideological rift introduced by Liberator Simon Bolivar and his second-in-command, General Francisco de Paula Santander.

Followers of the relatively conservative Bolivar with the support of the Catholic Church founded the Conservative Party in 1848 in response to the foundation of the secular Liberal Party, which was based on the British Enlightenment principles favored by Santander.

At the time, the current Republic of Colombia had not yet been founded.

The two parties were not just ideologically opposed, but were supported by and sometimes catered to distinct economically and politically powerful families.

The current President Juan Manuel Santos, for example, is a descendant of independence fighter Antonia Santos and a grand-nephew of President Eduardo Santos.

Attempts to consolidate political and economic power by these two powerhouses led to several violent confrontations, wars, and periods of political exclusion between the late 19th century and the 1940s.

Political control since 1810

The violence with more radically leftist forces did not take place until after World War II, when a populist liberal politician, Jorge Eliecer Gaitan, opposed the Conservative government and really began moving the masses, threatening the status quo the Liberal Party and Conservative Party had long benefited from.

Gaitan’s murder in 1948 sparked a period called “La Violencia,” a decade-long brutality in which between 150,000 and 200,000 Colombians were killed.

Deaths during “La Violencia”

The partisan violence ended in 1958 when the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party agreed to divide power, taking turns holding public office and controlling the economy every four years. This agreement was called the “National Front.”

The less pragmatic, more ideological left wing of the Liberal Party, joined by communists and influenced by a wave of socialism-influenced revolts across the continent, did not accept this National Front.In the countryside, where inequality was bordering extreme levels, farmers began revolting against the Bogota-based political elite.

From this movement sprung the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), who were initially nothing but a handful of peasants.

In 1964, they declared themselves independent, forming The Republic of Marquetalia in a tiny village on the foot of the Nevada de Huila mountain range.

History of the FARC

Fueling the violence with drugs

The conflict escalated in the 1980s when several leftist rebel groups became active, drug trafficking revenue was financing weapons across the country, and right-wing self-defense forces began forming to protect private interests from the increasingly powerful and wealthy guerrillas.

In hand with the Colombian Communist Party, the strengthened FARC began to have political ambitions at a national level, posing a serious challenge to the political status quo.

In 1985, the Colombian government began peace talks with the different rebel groups and the FARC joined more moderate leftist thought leaders to form a political party, the Patriotic Union.

Rebel groups M-19 and EPL decided to demobilize in 1991 after the government agreed to a new constitution.

However, groups like the FARC and ELN did not demobilize and did not agree with the new constitution.

The Patriotic Union — the rebels’ attempt to actively participate in politics — faced an extermination campaign by right-wing paramilitary groups and extreme elements within the state, particularly the military.

Additionally, the government created bad blood by attacking a FARC compound in the middle of the talks.

In turn, the FARC removed itself from politics and began an impressive territorial expansion, increasingly using the revenue from drug trafficking to fund their military campaign.

The group had also discovered a new form of making money that also served as political intimidation, kidnapping.

Kidnappings in Colombia

However, as the FARC in the mid-90s were approaching the gates of the capital Bogota from the south, state-aligned paramilitary groups from the northwest and east of Colombia united and formed the AUC and one of the bloodiest decades of the conflict began.

The state forces fighting the guerrillas were now supported by brutal paramilitary forces that began pushing the guerrillas back south while taking increasing control of the drug trafficking trade.

However, in spite of paramilitary pressure in the north, the FARC was able to make major territorial gains in the south of the country and, financed by drug trafficking and “economic retentions,” or kidnappings for extortion purposes, the FARC was able to grow stronger, increasing their territorial pressure to the point they were putting up roadblocks outside major cities.

Faced by the increasingly strong guerrilla group and an increasingly weak state, President Andres Pastrana (1998-2002) agreed to peace talks with the guerrillas in 1999 while obtaining US support for the military defeat of the FARC.

Meanwhile, paramilitary violence surged and groups united in the AUC in 1997 carried out a brutal offensive, breaking victimization records while the Pastrana administration was negotiating with the FARC.

The talks failed in 2002, and the military offensive supported by the 1999 Plan Colombia deal came into action.

Following the talks, the Colombian people elected Alvaro Uribe, a hard-liner whose family has had ties with paramilitary death squads, and Plan Colombia really came to full force.

The Colombian military gained access to arms and intelligence and was also increasingly able to push the FARC deeper inside the jungle.

The paramilitary forces demobilized between 2003 and 2006 and the military, now just with US support, since then fought the guerrillas on its own. By 2008, the FARC was at its weakest point and lost its founder, Manuel Marulanda, a.k.a. “Sure Shot.”

FARC fighters since 1985

However, the military successes claimed by the Colombian government of Alvaro Uribe and the US government of George W. Bush came with a major human cost; millions of Colombians were displaced. Tens of thousands civilians were killed or otherwise victimized.

Conflict victims since 1985

The US began pulling funds following a series on politicians’ ties to the AUC and the killings of thousands of civilians to inflate the military’s success rate, and the Colombian military was left on its own.

Additionally, the weakened FARC switched from the toxic territorial warfare with large armies to traditional guerrilla warfare using tiny units undetectable from the sky and easily hidden among the civilian population.

The conflict seemed to have reached a stalemate as the military’s effectiveness dropped while that of the guerrillas went up.

However, the Colombian government, under the leadership of former President Alvaro Uribe, began approaching the FARC after the demobilization of the AUC.

These initiatives did not result in either informal or formal talks until current President Juan Manuel Santos took office in 2010 and, while still at war, began secret peace talks with the FARC that resulted in the formal peace talks going on at the moment. These talks ended successfully and the FARC agreed to demobilize in exchange for judicial leniency for war crimes and temporary congressional seats.

Skip to

Top – The war – The talks – The deal – Disarming FARC – Reforms – Victims, truth and justice – Timeline – Resources

The talks

The initial approach between the FARC and the state made as early as 2006 when former President Alvaro Uribe in secret asked businessmen Henry Acosta to seek contact with “Pablo Catatumbo,” then the commander of the FARC’s Western Front and highly regarded within the guerrilla organization.

A second negotiator, Swiss scholar Jean Pierre Gontard, was also said to have been authorized to talk to the FARC by the Uribe administration in that year.

Acosta achieved to make contact with the FARC and begin a preliminary negotiation, but the attempt failed in 2007 because Uribe sought the guerrillas’ surrender while the FARC wanted a negotiated peace between equals.

Uribe then sought the mediation of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and leftist Senator Piedad Cordoba, but also without success.

Then-Peace Commissioner Frank Pearl, as instructed by president Uribe, tried to initiate a peace process with the FARC again in 2008, according to President Juan Manuel Santos, who was Uribe’s defense minister until 2009.

Santos secretly restarts Uribe’s secret peace talks

When Santos was elected president in 2010, Pearl became Housing Minister and Sergio Jaramillo, Santos’ former vice-minister, became peace commissioner.

The president called in the help of his brother, renowned journalist Enrique Santos, to join Acosta in secretly pursuing formal peace talks.

The first physical meeting between government representatives and the FARC, according to the guerrillas, took place in March 2011 near the Colombian-Venezuelan border.

Santos has claimed that then-FARC leader “Alfonso Cano” approached him personally to restart the talks. Santos agreed, but only if the talks remained “entirely confidential until [they] both decided when to go public.”

The death of ‘Alfonso Cano’

Because both parties were still at war and the peace talks were taking place in secrecy, the military and the FARC alike continued going after high-profile enemy targets.

The military killed Cano in November 2011, less than 10 months before the peace talks were formalized.

According to Cano’s successor, “Timochenko,” the air strike that killed Cano was a severe setback to the talks.

However, then Venezuelan President Chavez intervened and was able to convince the guerrilla leadership to continue negotiating, according to Timochenko.

Within days, Acosta told Reuters, the FARC leadership sent him a message: “Tell the president everything we have discussed stands, this does not affect the dialogue.”

From then on, the negotiators moved towards formulating the points on the agenda of the formal phase of the talks and in February 2012, the FARC renounced kidnapping as a token of the group’s commitment.

By August 2012, the talks were close to being formalized and were made known more widely within the government.

Former President Alvaro Uribe, who since leaving office in August 2010 had become a political enemy of Santos for both political and ideological reasons, received classified information about the talks and publicly announced that Santos and the FARC were talking on August 19, 2012.

While the Santos administration publicly denied Uribe’s rumor, the negotiators rushed to finalize the formalization agreement of the talks and Santos traveled to Cuba to sign the “General Agreement for the Termination of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace” on August 27, according to the FARC.

Talks made public

A day later, the president confirmed that his administration had indeed been holding exploratory talks with the FARC.

On September 4, Santos appeared on television to announce that an accord had been signed to begin formal peace talks.

Timochenko appeared separately on television to confirm the agreement. While the FARC objected,

The Colombian government lifted 191 arrest warrants in order for 29 FARC negotiators and their assistants to participate in the talks that kicked off ceremonially in the Norwegian capital of Oslo in October.

The FARC’s negotiators traveled then directly to Havana, Cuba, where the talks would be held.

The government delegation returned to Bogota until November 19 when the formal talks began with a six-point agenda seeking to address the causes, aggravators and consequences of the conflict.

The formal talks

The negotiators agreed to hold the negotiations without declaring a ceasefire, much to the dislike of the FARC.

The administration of former President Andres Pastrana did agree to a ceasefire in 1999 and demilitarized an area the size of Switzerland, but those talks failed in 2002.

During the ceasefire, the guerrillas had taken major military advantages, which is why Santos rejected a ceasefire ahead of the talks.

This decision later proved an extremely risky one as high-profile attacks of the guerrillas ended up discrediting the talks and at one point even threatened to blow them up altogether.

Easy part first

The beginning of the talks were easy. As a sign of goodwill, the FARC declared a two-month unilateral ceasefire in the hope for reciprocation, but with no response.

When in late January 2013 the FARC’s ceasefire ended, the guerrillas took to the offensive and began a series of mutual attacks that would later undermine the continuity of the talks.

The two parties initially stuck to the promise that what happened on the battlefield would not influence what happened in Havana.

But when 19 soldiers were killed in a FARC attack, Santos allegedly was close to ending the peace talks altogether. It would not be the only time.

Disregarding the distortion from the battlefield, the first two points on the agenda, rural reform and political participation, were easily agreed. By the end of 2013, draft agreements on both points had been announced.

The deals sought to solve some of the main causes of Colombia’s armed conflict, extreme inequality on the countryside and the systematic exclusion of the left in politics.

During the negotiations, the government and the FARC decided to bot yet discuss the “End of Conflict” yet, but proceed with “The Problem of Illicit Drugs,” or the FARC’s participation in the country’s drug trade, which would be agreed on on May 16, 2014, only 18 months after the beginning of the talks.

Opposition conspires with military to sabotage talks

While the negotiators were about to touch the most delicate points on the agenda, “Victims,” opponents of the talks began to conspire in an attempt to discredit the talks ahead of the 2014 elections in which Santos sought reelection, but former Uribe wanted a president of his own party, Oscar Ivan Zuluaga.

Uribe’s party, the Democratic Center, teamed up with a political hacker, Andres Sepulveda, and dissident elements within the military.

Reportedly using CIA-provided equipment, rogue elements within the Colombian military set up a spying program, “Andromeda,” that intercepted communication from the FARC’s peace delegation.

This information was then sold to Uribe’s party that would leak classified information to undermine the credibility of the talks.

The strategy almost worked and Zuluaga won the first round of the elections. However, Santos’ efforts to negotiate out of a war was so broadly supported in Congress that the leftist coalition urged its constituency to vote for Santos, who won the second round.

Additionally, with only five days before the elections, Santos and the ELN, Colombia’s second largest rebel group, announced they were also engaged in preliminary peace talks.

This pushed the electoral preference to Santos’ favor and he defeated Zuluaga in the second round.

Since then, the Democratic Center has found itself in increasing legal trouble over the illegal spying and the making public of classified information.

The hard part

The negotiators had earlier agreed to postpone negotiating End of Conflict until later, which proved one of the most controversial decisions.

The two negotiation teams needed only 18 months to come to agreements on rural reform, political reform and drug trafficking, but how to actually end the war and provide justice for victims proved much more difficult.

Ultimately, “Victims” and “End of Conflict” would take the negotiators 28 months.

The negotiations on victims partly took some time because victims were asked to actively participate in the proposition of the deal. In Colombia, three victim forums were held and the representatives of 60 victim organizations were invited for input.

However, this point also included taking responsibility for the tens of thousands of war crimes by both parties and neither party was going to take responsibility for crimes committed by both.

The FARC, additionally, refused to accept prison sentences.

While negotiators were stuck on the subject in Havana, violence in Colombia escalated and threatened the continuity of the talks.

In order to prevent the talks from failing, the FARC announced a unilateral ceasefire and the government announced an end to airstrikes.

But on April 15, a FARC unit in western Colombia surprisingly attacked a nearby stationed military unit, killing 11.

The incident spurred Santos to resume airstrikes after which the FARC ended their unilateral ceasefire.

The commanders of the military unit were later sacked amid growing rumors both they and the guerrilla unit had been working for local drug traffickers.

The foreign guarantor countries, Cuba and Norway, were able to convince both the FARC and and the government to agree to “de-escalation measures”

The FARC almost immediately stopped all attacks and the military gradually reduced the attacks on FARC camps.

In November, FARC leader “Timochenko” said the FARC would no longer be purchasing weapons.

By December 2015, a year after victims were first discussed, the FARC and the government announced agreement on this crucial point.

But the deal spurred public resistance because, rather than prison, war criminals who fully cooperate with justice would be granted alternative “restrictions of liberties.”

At the same time, the agreement received praise for another clause that obligates guerrillas and members of the military convicted of crimes to repair their victims by physically repairing the damage they had caused.

Since then, both the FARC and the government have made several visits to victims to ask forgiveness for war crimes committed by both warring parties.

The end of conflict game

Once agreement on victim reparation and justice was found, the talks entered a rapid.

Timochenko ordered an end to the recruitment of underage FARC fighters in February and agreed to the release of child soldiers ahead of a peace deal.

Colombia’s congress began the preparations of legislation necessary to allow the FARC’s demobilization and by June 23, in front of international press, Santos and Timochenko shook hands on a definite bilateral ceasefire, effectively ending the armed conflict.

On August 24, the negotiators formally unveiled the agreement to end 52 years of conflict that has left more than 265,000 Colombians dead, 45,000 missing and 7 million displaced.

The deal was formally signed on September 26 in Cartagena, but rejected by Colombia’s voters in a referendum on October 2.

Following the shock rejection, the government entered in negotiations with opponents of the deal, primarily former President Alvaro Uribe, evangelical pastors, military commanders and FARC victims.

Following these negotiations, a revised deal was reached on November 10, signed on November 24 and ratified by Congress on November 30.

Skip to

Top – The war – The talks – The deal – Disarming FARC – Reforms – Victims, truth and justice – Timeline – Resources

The deal

The 310-page document that was negotiated in the talks essentially seeks to transform the FARC from an armed group to a legitimate political movement, but it pretends to do much more.

To ensure Colombia never will have to go through the levels of drug-fueled political violence again, parts of the deal focus on political and rural reforms that ought to remove the conditions that have led to the extreme violence Colombia has gone through.

Additionally, the deal seeks a radically different approach to combating drug trafficking. The government and the FARC believe to achieve this through active and economic support for coca farmers who want to substitute their crops for legal produce, major investments to improve living conditions in the countryside and the combating of ongoing ties between the country’s elites and drug-trafficking groups formed after the partially failed demobilization of paramilitary organization AUC between 2003 and 2003.

In accordance with the peace talks agenda, the final deal between the Santos administration and the FARC consists of six points; “Comprehensive agricultural development policy,” “Political participation,” “End of the conflict,” “Solution to the problem of illicit drugs,” “Victims” and “Implementation, verification and countersignature.”

Rural reforms

The agreement on rural reforms essentially try to curb extreme inequality on the countryside while embarking on investments that make Colombian farmers both more self-sustainable and more competitive in an increasingly globalized economy.

Additionally, it seeks to redistribute land to the benefit of poor farmers and the restitution of almost 15% of the country’s entire territory that was stolen during the conflict, mainly be paramilitary groups in collusion with the military, corrupt state officials and rural businesses.

To achieve this, the government vowed to create a land fund from where landless or displaced farmers can request land titles for agricultural plots that are in in the fund.

The land from this fund will come from stolen land that has been recovered from its new owners, but will also seek the seizing of underused private land property of large land owners and the privatization of state-owned land.

The rural reforms go hand in hand with the agreement of drug trafficking as many farmers depend on the cultivation of coca because they can not take part in the regular economy.

Partly due to chronic state neglect and partly because of the destruction caused in the war, many farmers have no access to normal infrastructure that allows them to deliver their produce to the market before it rots.

The deal vows to improve this infrastructure and allow small farmers access to the market.

Political reforms

The political reform has two purposes. It seeks the FARC’s transition from an armed group to political movement and make Colombia’s political system more inclusive for people and organizations who make no part of the elites that have controlled politics for centuries.

Ever since before the armed conflict, many politicians who challenged the status quo in politics were assassinated, including iconic democratic leaders like Jorge Eliecer Gaitan and Luis Carlos Galan.

When the FARC first trying to go legit, elements within the state conspired with paramilitary death squads and killed thousands of members of the Patriotic Union party that the FARC wanted to become part of.

This and ongoing electoral corruption has left Colombia’s electorate disenfranchised and has spurred the formation of armed groups like the FARC and many others after them.

To allow the FARC’s transition to politics, the guerrillas will be allowed to take part in the 2018 elections, but with five guaranteed seats in both the Senate and the House of Representative for two terms. After these two terms, the FARC, like any other party, will have to campaign for a stake in Congress.

To secure the immediate inclusion of communities marginalized by the conflict, six more transitional seats will be made available to raise the voice of those most affected by the armed conflict.

The deal also includes a number of measures that seek improved protection of leftist groups, dissidents and rights defenders, who have been killed by the thousands, mainly by state-aligned paramilitary forces.

Drug trafficking

Colombia has been the world’s largest cocaine producer for decades, partly with the help of the FARC, who have been providing security to smaller drug trafficking groups and in some cases had their own routes to smuggle cocaine to one of the consumer countries in the north.

The guerrillas are not just obligated to fully abandon all illegal activity, including drug trafficking, they have also agreed to actively help authorities dismantle cocaine labs and help coca farmers substitute their crops for legal produce.

The government has committed to a less repressive approach to coca farmers and a more aggressive approach to drug trafficking organizations and their allies.

So, while coca farmers will be allowed to voluntarily take part in a government-funded crop substitution program and enjoy improved infrastructure, the higher echelons of the trade, the traffickers and money launderers, will be dealing with strengthened and more aggressive authorities.

Victims

The victims deal, which includes punishment for war crimes, consist of a comprehensive plan to provide truth to the country in general, and reparation and justice to victim.

It has been set up with the active participation of victims, a novelty in global conflict resolution.

Rather than being based on a punitive justice system that prioritizes the punishing of victimizers, the deal is based on the principles of restorative justice, which prioritizes the needs of victims and reconciliation.

More importantly, the deal pretends to guarantee non-repetition of armed conflict in a country that’s been plagued by waves of political violence and armed conflict since the 1940s.

Amnesty court

To do this, the victims deals contains the coming into force of a transitional justice system with three bodies, an Amnesty Tribunal that grants full judicial amnesty to FARC guerrillas who are not suspected of war crimes. Rather than receiving punishment, they will be taking part in a reintegration program.

Transitional Justice Tribunal

A Transitional Justice Tribunal will investigate all accusations of war crimes and other grave human rights violations. Based on the allegations provided by the prosecution and victims, this court will find those criminally responsible.

The most controversial part of this court is the leniency granted to convicted war criminals if they fully and without hesitation cooperate with justice. According to Human Rights Watch, this tribunal would not provide “justice for atrocities.”

Convicted war criminals who are able to obtain full benefits can evade prison and be sentenced to “restricted liberties,” and if appropriate, be convicted to physically repair the damage done, for example, by helping remove a minefield from a town.

Convicts who tell the truth but after hesitation lose the possibility to evade prison and can be sentenced to prison for periods between five and eight years.

War criminals who refuse cooperation face prison sentences up to 20 years.

The court is expected to try hundreds of guerrillas, 24,400 state officials and 12,500 civilians.

Truth Commission

A Truth Commission will take force to, simultaneous to the transitional justice tribunal, seek to clarify the truth about the conflict that has maintained an exaggerated impunity rate for decades.

Tens of thousands of war crimes, the majority alleged to have been committed by the state itself, have never been solved. Others were never asked forgiveness for.

This is mainly because the conflict provided the perfect pretext for the use of political violence that killed thousands. Others used the conflict as pretext to maximize profits by using the armed actors to intimidate or kill labor rights workers.

Additionally, more than 45,000 Colombian families are still seeking closure about disappeared loved ones.

Because the Truth Commission’s priority is clarifying the truth, its evidence may not be used in criminal cases. This increases the chances of war criminals providing closure to victims, without this influencing their criminal case in the Transitional Justice Tribunal.

Reparation

The deal on victim reparation seeks to contribute to already existing legislation like the current Law for Victims and Land Restitution. In all cases of reparation, victims will actively participate to secure their rights are served and their victimization is compensated by their victimizer.

The purpose of this is to promote the re-establishment of the dignity of the victims, reconciliation and the peaceful co-existence of civilians and former guerrillas.

In order to achieve this, the FARC, the government and private entities that have promoted victimization will have to take part in public acts in which they assume responsibility for suffering caused and ask their victims for forgiveness.

The FARC also agreed that their demobilizing fighters will provide free labor and reconstruct destroyed infrastructure, prioritizing areas most affected by the 51 years of warfare. Additionally, the guerrillas agreed to help in the clearance of landmines, help coca farmers in crop restitution programs and participate in, for example reforestation programs, where FARC attacks left environmental damage.

The government has promised to promote the participation in reparation efforts by state agents or state-aligned private actors like ranchers who financed the formation of paramilitary groups.

Additionally, the rural reform agreed on by the warring parties will prioritize the return of lost property to displaced people, who make up the vast majority of victims.

Colombians who have fled the country will receive government support if they want to return.

The government will spearhead projects that seek the psycho-social rehabilitation of victims. Part of this is the government’s assumption of responsibility in areas long abandoned by the state. This increased state presence should also prevent illegal armed groups from emerging in areas where state abandonment has left a power vacuum long filled by the FARC.

Any Colombian who considers himself a victim of the conflict will be able to request to be repaired.

Guarantees of non-repetition

Some of the guarantees of non-repetition, including the crucial disarmament of the FARC, will be defined in the last point on the peace talks agenda, End of Conflict.

Others have already agreed before in deals on rural reform, political participation and drug trafficking.

Rural inequality and political exclusion are widely seen as some of the main causes of the conflict, while drug trafficking has been one of the main aggravators of victimization because its revenue fueled the buying of arms by illegal armed groups.

As part of the victims deal, the Colombian government has promised and begun campaigns that seek to protect human rights defenders and undo decades of stigmatization as part of war propaganda.

The public will increasingly be informed on what human rights are, what they are for and how to appeal to justice in cases of violations.

Human rights defenders will receive increased government support to carry out their work, particularly in rural areas.

The state, long accused of disregarding its citizens’ human rights will also formulate a National Human Rights Plan and guarantee the safety of those who want to organize protests.

The Ombudsman’s Office will be strengthened and be responsible for helping other state entities in securing Colomban citizens’ basic rights.

Skip to

Top – The war – The talks – The deal – Disarming FARC – Reforms – Victims, truth and justice – Timeline – Resources

Disarming the FARC

The FARC’s demobilization and disarmament process is a 180-day process after which all guerrillas and militia members be either in court or in a rehabilitation program.

The process began immediately after the signing of the peace deal, under the supervision of the United Nations and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, and according to a strict timetable.

So far, only the FARC’s First Front has refused to take part in this process. Other fighter units have either supported the peace talks or remained quiet ahead of the deal.

In total, the FARC vowed to demobilize some 17,000 men and women, of whom 6,600 were armed fighters.

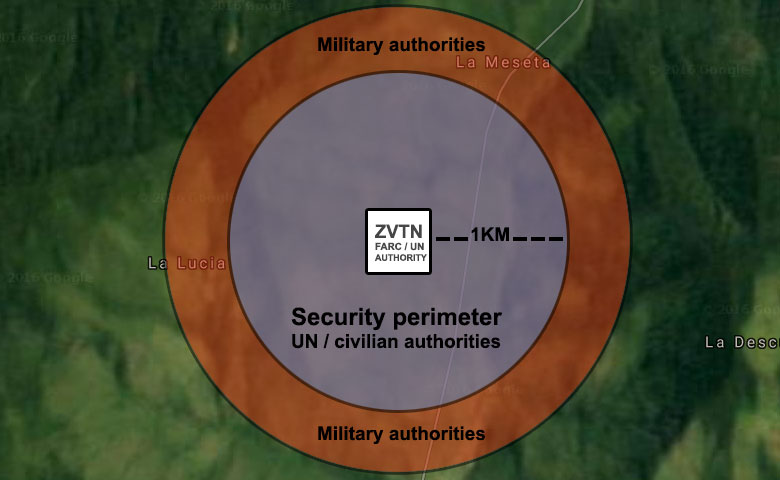

To facilitate this, the government, the UN and the CELAC created 20 transitory areas called TVZTs where the guerrillas initially will concentrate and seven camps where the guerrillas will stay while their legal situation is being considered by the amnesty court.

Within the veredas, the legal carrying of firearms will temporarily be suspended for the maximum of six months after which the guerrillas’ legal situation should be resolved and the ZVTN be lifted.

During this six-month period, a safety cordon of approximately one kilometer has been created around these ZVTN to prevent any type of armed action possibly committed against demobilized guerrillas or the local population.

Within the zone, no member of the security forces may be present, only member of the FARC and UN personnel.

Within the safety cordon around the ZVTN, public and ex-guerrilla security will be overseen by the international observers. No members of the security forces or the FARC will be allowed inside the safety cordon.

The ring surrounding this cordon will have increased presence of both the military and the police.

One day after the signing of a peace agreement, the government will give out concrete instructions to the military that will allow the mass displacement of FARC members to the ZVTN where they will be held for the duration of their demobilization and disarmament.

Five days after the peace deal, the commanders of the so-called “Tactical Units” of the FARC will move to these designated areas and begin the actual mass demobilization of troops and arms in coordination with the United Nations and local civilian authorities. The military will be informed indirectly to create safety corridors for the demobilizing guerrillas.

Former guerrillas who do not show up at the demobilization points before they are lifted will be in violation of the peace deal and continue to be targets for the authorities.

With the exception of rebel representatives, the former guerrillas will not be allowed to leave the camp or have any contact with the civilian population until after their demobilization and disarmament.

Disarmament

The UN will be fully responsible for the disarmament of the FARC, a process that must be finish within 180 days after a peace deal.

On the first day after the deal the FARC surrenders all its documentation on landmines, allowing the military coordinate the years-long effort of clearing these minefields with the help of the guerrillas.

From the fifth day of the deal, the United Nations will begin asking FARC’s fighters units to surrender an inventory of the arms in their possession.

Once all arms are surrendered, they will be made useless and converted into three monuments remembering the conflict and its victims. One of the monuments will be placed inside the UN’s main office in New York City, one in Cuba and one in Colombia’s national territory.

The Tactical Unit commanders will be responsible for the FARC’s compliance and will have to hand over this information on the fifth day they arrive in the demobilization areas.

Additionally, these commanders will give up detailed information on the location of minefields and unexploded ammunition or bombs. This will subsequently be verified by the UN.

Between day seven and day 30 after a peace accord, FARC members will actually and begin bringing their weapons to the 23 established ZVTN.

The arms will then be stored inside UN-controlled warehouses that will begin the making useless of the weapons between day 10 and day 60 after the deal.

After day 60 the UN will begin taking weapons away from these camps.

Between day 90 and day 150, the guerrillas will fully disarm. The FARC will have another 30 days just in case, but after day 180 no arm may be in the possession of any of the guerrillas.

This is also the day that all guerrillas must be taking part in either their trial or reintegration program after which all ZVTN areas should be guerrilla-free and the local situation be normalized.

Additionally, the six-month period is also the maximum period for the bilateral ceasefire, meaning that any guerrilla still in arms will be in violation of the agreement and thus expect police or military action.

FARC demobilization an disarmament timeline

Skip to

Top – The war – The talks – The deal – Disarming FARC – Reforms – Victims, truth and justice – Timeline – Resources

Reforms

Colombia’s Congress has already approved the “Legislation for Peace,” which gives President Juan Manuel Santos extraordinary faculties to pass laws and reduces the possibility of Congress to either delay or alter agreements made with the FARC.

As part of the agreement with the FARC, the government will embark on a number of reforms, mainly in agriculture, but also in politics in order to make it more inclusive and to allow the FARC their promised temporary participation.

However, the government first must pass an amnesty bill that allows the effective amnesty of the former FARC members who are not accused of war crimes.

Political reforms

The political reforms are meant to “contribute to the amplification and deepening of democracy, implying the abandonment of arms and the proscription of violence as a means of political action,” according to the peace deal.

Additionally, “in order to consolidate peace, it is necessary to guarantee pluralism, facilitating the constitution of new political parties and movements that contribute to debate and the democratic process, who must have the necessary guarantees for the exercise of opposition and become true alternatives for power.”

While the FARC are secured 10 seats in Congress between 2018 and 2022, the majority of the lasting reforms are to promote political inclusion.

One of the most important changes is the creation of six congressional seats for conflict areas to secure an immediate inclusion into national politics of the country’s poorest regions that have long suffered state abandonment.

In order to reduce violence against extra-congressional political movements like human, labor, civil or minority rights organizations, a special “Integrated Security System for the Exercise of Politics,” which is meant to both prevent violence, protect political actors and activists, and investigate acts of political violence.

To curb recurring social unrest and the escalation of violence during protests of strikes, the government will create a Commission of Dialogue, which is to function as a mediator between authorities and social organizations in the case of conflict.

The government also vowed to create a “National Council for Reconciliation and Coexistence” that will promote tolerance and non-stigmatization, especially socially and politically.

Additionally, the government vowed to modify Territorial Planning Councils to increase citizen participation and oversight in the bodies responsible for the country’s territories.

The threshold to become a political party will also be lowered, allowing smaller parties access to government funding of their political campaigns.

Rural reforms

The rural reforms might be the most far-stretching of all as they include the confiscation of private property, if anything a controversial issue.

However, reforms to improve unbearable living conditions and staggering inequality on the countryside have been in the making since the 1930s and have repeatedly been urged by international organizations like the United Nations.

Inequality in Colombia is so extreme, according to the UN, that less than 1% of the population owns more than 50% of the country’s land property. Meanwhile, small farmers massively turn to coca growth because they are unable to compete in the globalized market.

This is why a number of the rural reforms are specifically meant to reduce incentives to grow coca and increase incentives and conditions to either be self-sustaining or participate in the commercial agricultural sector.

More importantly, the government needs land for the 7 million displaced victims, most of whom had their land stolen.

Consequently, the priority of the reforms will be “the deconcentration and promotion of more equitable land distribution.”

To do this, the government will create a land fund consisting of 3 million hectares to be distributed freely in the first 10 years after its creation among landless farmers.

This land will come from plots that belong to the state, are voluntarily donated by large landowners friendly to the process or are successfully seized, for example from convicted drug traffickers or from large land owners whose land is deemed “unexploited.”

The government will also create a subsidy program for landless farmers seeking to buy land property.

What might be an even bigger initiative is the formalization of the titles of plots of land that in some cases have been worked by families for generations without ever being formalized as their private property.

Additionally, the government will create a government agency that mediates in the cases of land ownership disputes, making sure they are dealt with by a judge and civilians don’t take justice in their own hands.

The government also vowed to be stricter in reducing the territory potentially available for oil and mining, and impose adequate protection measures for the country’s flora and fauna.

Skip to

Top – The war – The talks – The deal – Disarming FARC – Reforms – Victims, truth and justice – Timeline – Resources

Victims, truth and justice

Colombia’s conflict has left more than 8 million victims. Political violence that’s been wreaking havoc since the 1940s has left at least half a million Colombians dead. The justice deal agreed between the government is not to just bring justice to the victims, but also break this cycle of violence.

Rather than being based on a punitive justice system that prioritizes the punishing of victimizers, Colombia’s transitional justice system is based on the principles of restorative justice, which prioritizes the needs of victims and reconciliation.

More importantly, the deal pretends to guarantee non-repetition.

To provide justice for the victims, an international Transitional Justice Tribunal and a Truth Commission will take force.

The truth commission’s main purpose is to bring closure to victims and figure out who is responsible for what.

At the request of either itself or victims, the commission can cite alleged war criminals to testify and explain what led to their crimes.

The commission has no judicial authority and evidence or testimonies gathered by that commission may not be transferred to the Transitional Justice Tribunal. This allows alleged war criminals to come clean with their victims without being inhibited by the possibility their words could be used against them.

The justice tribunal will conduct criminal investigations of all pending and incoming criminal complaints about war crimes and crimes against humanity.

This court is expected to investigate hundreds if not thousands of guerrillas, 24,400 convicted or alleged state war criminals and some 12,500 private individuals and companies suspected of supporting war crimes.

FARC rebels with no suspected human rights record will have to appear before an amnesty chamber after which they will take part in reintegration programs that should support the communities victimized by the conflict. Those guerrillas who are convicted of war crimes will be able to spend a maximum of eight years outside of prison, but under “restricted movement,” but on the condition they fully collaborate with justice.

Convicted war criminals — guerrillas, members of the military, politicians and civilians alike — who only partly helped in the clarification of their crimes will serve prison sentences of no longer than eight years. War criminals who refuse collaboration can face sentences up to 20 years in prison.

To further promote the rights of victims, a Victims Fund and a Land Fund will be created to financially compensate victims of violence and provide land to the millions of small farmers who were displaced during the conflict.

Each Colombian who considers himself a victim can ask for help from these funds. More on this type of victim compensation can be found in the chapter “The deal.”

Skip to

Top – The war – The talks – The deal – Disarming FARC – Reforms – Victims, truth and justice – Timeline – Resources

Timeline

2016

September 26 – President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC leader sign peace.

September 27 – Guerrilla representatives gathered in Yari, Caqueta return to their fronts to begin the preparation of their units’ demobilization and disarmament while the government gives concrete instructions to the military on how to facilitate the safe demobilization of the FARC, set to begin on October 3.

October 2 – Colombia’s voters reject the peace deal in a referendum, effectively halting the peace process and spurring negotiations over a revised deal between the government and opponents of the deal.

October 3 – Negotiations with opponents of the rejected deal begin.

October 17 – President Santos imposes an October 20 deadline on the receiving of revision proposals.

October 20 – Government says no more proposals will be received and negotiations to revise the rejected accord begin.

October 22 – To prevent a possible mass desertion of FARC guerrillas who are uncertain about their future and attacks on rebel units, the government and guerrilla leadership agree to create pre-demobilization camps.

November 7 – The United Nations resumes its verification and monitoring of the ceasefire after its mandate had been withdrawn by the October 2 referendum.

November 10 – Negotiators of the government and the FARC announce to have reached a new deal.

November 16 – Members of the military kill two FARC guerrillas in the first breach of the ceasefire since the initial peace deal was agreed. The UN-led verification and monitoring mechanism that also consists of a FARC and a military representative begin investigation and admit join responsibility for the breach two weeks later.

November 24 – In a sober ceremony, President Santos and FARC leader Rodrigo Londoño, a.k.a. “Timochenko,” formally sign the new peace deal.

November 30 – Colombia’s Congress unanimously approves the peace deal after the conservative opposition boycotts the vote, claiming Congress does not represent the people and the revised deal must be ratified in a second referendum.

December 1 – Formal first day of peace between the government and the FARC.