Colombia’s prosecution allegedly used foreign aid to convert its organized crime division into a unit that apparently persecutes protest organizers.

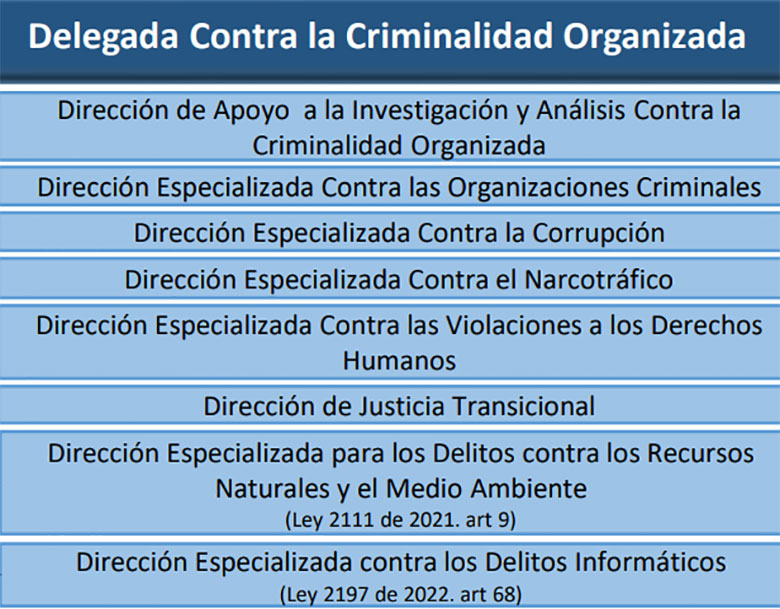

The organized crime division was created in 2017 to strengthen the prosecution’s capacities “in the fight against 1) organized crime, 2) corruption, 3) drug trafficking, 4) human rights violation, among other things” as part of an ongoing peace process.

Instead, the unit of organized crime prosecutor Javier Garcia has been seeking the mass prosecution of people who took part in mass protests against former President Ivan Duque in 2019 and 2021 on criminal charges that include terrorism.

Garcia would know as much about criminal law as the next guy as the former law school buddy of Prosecutor General Francisco Barbosa studied administrative law at the disgraced Sergio Arboleda University.

Sergio Arboleda University: educating Colombia’s mafia

Bad law or bad politics?

The prosecution’s organized crime unit failed to successfully prosecute a single member of one of Colombia’s illegal armed groups in the past year, according to the prosecution’s annual report to Congress.

Instead, the unit of the former law school buddy of chief prosecutor Francisco Barbosa has been trying to prosecute more than 170 of the more than 2,000 people who were arrested during and after the protests that erupted in April last year.

The mass arrests and attempts to press charges were rejected by judges, but DEDOC was able to secure five convictions, despite the apparent help of its newly founded “Elite Group Against Terrorism”(GECET), according to investigative journalism website Cuestion Publica.

Human rights defenders have lambasted the prosecution for failing to prosecute cops accused of assassinating between 25 and 44 people during the protests while allegedly fabricating charges against protesters who allegedly joined so-called “Primera Linea” groups to protect others against deadly police violence.

Colombia desperately implies peaceful protesters were armed to the teeth

One Medellin resident was arrested in July last year and charged with terrorism for broadcasting protests live on social media “in which he would have instigated violence,” according to Garcia, whose team has yet to call the protester to trial.

The United Nations’ human rights chief in Colombia, Juliette de Rivero, rejected the stigmatization of the Primera Linea groups in September, stressing that criminal charges like “conspiracy and terrorism, according to international norms and human rights standards,” were “excessive.”

Dozens of arrested protesters have been waiting to be called to court for more than half a year while judges ordered the release of dozens who were called to court on trumped up charges.

In a report to Congress, the prosecution praised the help of GECET, and the newly founded “counterterrorism” agencies CI3T and GRATE of police intelligence unit DIJIN for imprisoning the protesters.

Colombia seeks controversial new spy agency to confront ‘terrorist threat’

The prosecution mess

The prosecution has made an utter mess destroying its organized crime unit in its apparent attempt to criminalize peaceful protest and all but legalizing police killings.

In an April 2020 letter to the United Nations, the Duque administration denied that the DECOC was supposed to dismantle illegal armed groups and reduce organized crime, but was created for the “persecution of terrorism and associated crimes,” including the “violent radicalization of university students.”

Seven months later, Duque and Barbosa announced the creation of an elite group to fight “sophisticated organizations” with an “urban war doctrine based on the recruitment of youth” that sought “chaos” by “infiltrating social protests.”

Whether they were talking about the CEGET is uncertain as the alleged 2018 decree that created the unit and the alleged January 2020 resolution that laid out its priorities are missing from online government archives.

In fact, the CEGET doesn’t even appear anywhere on the prosecution’s official organizational chart.

Foreign support?

According to the prosecution, its “counterterrorism” unit that is accused of political persecution received the support of the European Union in 2019 when the CEGET had yet to formulate its priorities.

The United Nations’ Counter-Terrorism Center began cooperating with the CEGET in 2020 already, the prosecution told Congress.

The International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs Section of the United States of the American embassy in Bogota is preparing a training for the 21 alleged prosecutors of the alleged anti-terrorism unit and spent almost $23 million since 2019 on the organized crime unit and the Special Investigations Unit (UEI), which was created in 2017 to investigate the mass killing of social leaders, according to the prosecution.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken confirmed last year that American support for Colombia included “training local prosecutors and judges so they have the capacity to try and win cases,” but said nothing about helping the prosecution unit accused of persecuting political activists.

Military intelligence spied on protest organizers in Colombia, US and Europe

Domestic opposition

Barbosa’s persecution of protesters and failure to effectively prosecute cops accused of homicide has created major tensions with President Gustavo Petro, who has called the detained protesters “political prisoners.”

In an attempt to free the allegedly arbitrarily detained protesters and social leaders, Petro proposed to convert presumably innocent “peace promoters,” which would allow them to get out of jail.

The Prosecutor General insist that the Primera Linea is the legal equivalent of a terrorist organization and suggested that people who were arrested for their participation in protests last year could be hardened criminals.

At least one Bogota youth leader said the prosecution’s stigmatization and alleged assassination plots forced him to join the guerrillas.