The death of Colombia’s defense minister on Tuesday severely disjointed the government of President Ivan Duque, which was already struggling with public security and the coronavirus.

Defense Minister Carlos Holmes Trujillo was not just the country’s defense minister, but also one of the most senior members of Duque’s far-right Democratic Center (CD) party and a long-time ally of the president’s political patron, former President Alvaro Uribe.

Trujillo’s importance

Apart from the institutional consequences, the defense minister’s dying from COVID-19 is a tremendous blow for both the government and the ruling party of which Trujillo was a founding member.

While widely considered inept, Trujillo wielded enormous power and was one of the main forces keeping Duque’s government in line with his far-right Democratic Center party after the resignation of former Interior Minister Alicia Arango in December.

Uribe, the undisputed leader of the CD, was forced to resign from the senate in August last year after the Supreme Court placed him under house arrest on fraud and bribery charges.

Duque’s allegedly criminal patron was able to have the house arrest revoked, but can not return to the senate and is now facing three criminal investigations.

With Uribe out of the Senate and possibly wiretapped by the Supreme Court on election fraud suspicions, Arango in Geneva and Trujillo dead, Duque has run out senior “Uribistas” in his cabinet with the exception of Foreign Ministry Claudia Blum, who reportedly also wants to leave the cabinet.

The Defense Minister was rumored he wanted to run for president next year for the “Uribistas,” who might want to prepare for an electoral train wreck because of the abysmal approval of both Duque and Uribe.

The former president and former Medellin Cartel associate may have to team up with the notoriously corrupt Char Clan from Barranquilla to have any chance for cabinet positions and influence over the prosecution.

Dodgy clans with mafia ties tighten grip on Colombia’s congress

Vaccination nerves

While the country came out of its initial shock, criticism arose that if the Military Hospital couldn’t even save the defense minister’s life, what kind of healthcare ordinary Colombians may expect if they fall ill.

Most urgently, voices suggested Trujillo may still be alive if controversial Health Minister Fernando Ruiz had been able to obtain vaccines earlier like other Latin American countries like Chile and Panama.

Vaccine progress in the Americas

Ruiz previously said he received one shipment from US manufacturer Pfizer and another from COVAX vaccines that has been developed with the coordination of the World Health Organization.

Caracol Radio reported on Tuesday it had seen a draft decree specifying that the first Pfizer vaccines would arrive in the first week of February and that the COVAX vaccine wouldn’t arrive until March, later than promised.

The first Pfizer batch would allow the vaccination of 1.7% of the population, but when the National Vaccination Plan would effectively kick off appears to be still unknown.

Meanwhile, multiple pharmaceutical companies who have created vaccines against the coronavirus appear to be running into trouble to meet contractual obligations, particularly in Europe.

National Vaccination Plan schedule

Public security crisis

The defense minister’s death came two days after the opposition asked to replace acting Defense Minister and Armed Forces commander General Luis Navarro for a civilian minister.

Around the time of Trujillo’s death, the war crimes tribunal, Human Rights Watch and conflict analyst Ariel Avila ran the alarm that the public security policy of Duque and his late minister consisted mainly of holding press conference.

Avila warned that Duque’s bungling of a peace process with demobilized FARC guerrillas and his failure to formulate a proper security policy had created the “perfect storm” that could result in a further escalation of violence later this year.

Duque’s misrule: Colombia in ‘perfect storm’, heading towards ‘a river of blood’

The late defense minister spent the entire last year boosting the notoriously ineffective forced eradication of coca and promoting the resumption of aerial spraying to stop the booming cocaine trade, but whether this made any sense won’t be known until June.

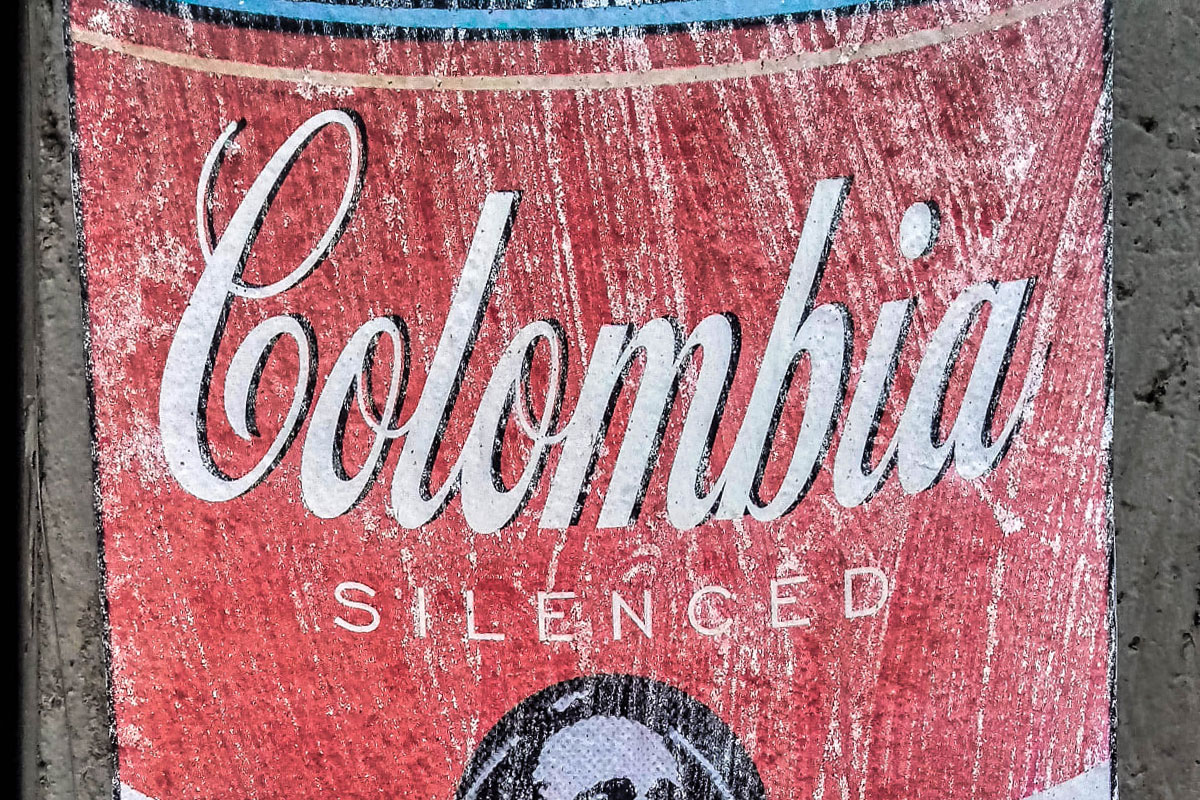

Interdiction statistics from South America and Europe indicate that Colombia’s cocaine factories may have produced another record amount of the popular white powder last year while Duque’s promotion of corrupt Uribe allies in the security forces may have made the National Police and the National Army powerless if not major associates of drug traffickers.

All this was already deteriorating when Trujillo was still alive. Whether Duque will be able to find a capable replace the late defense minister by someone from within his party, which has its roots in the Medellin Cartel, is entirely uncertain.

The president is already widely considered Colombia’s worst ever president. The previous holder of this dubious title was Andres Pastrana who was president in the late 1990’s when the state all but failed.