Colombia’s Conservative Party (PC) is traditionally one of the country’s largest political organizations and has dominated Colombian politics since the 19th century.

The party can be best understood through its most enduring values. It’s most controversial core principle is an unwavering fidelity to the Catholic Church. This also converts into belief in tradition, the family as the foundation of society, and the opposition to a separation of church and state.

From its creation in 1849, the Conservatives have opposed dictatorship, Communism and all Communist principles. The party has built its foundation on free trade, private property and legal liability.

The party was born in opposition to the 1845 election of President Jose Cipriano, a staunch supporter of English liberal political philosophy from the enlightenment period, who abolished slavery and persecuted the Catholic Church. Supporters of Cipriano founded the Liberal Party, Colombia’s other political powerhouse, in 1948.

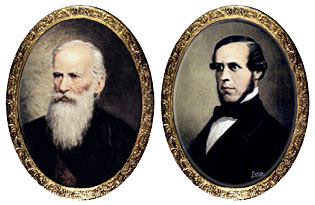

In a response, detracting liberals, prominent landowners and Catholic Church authorities founded the Conservative Party in 1849.

Before forming their political parties, wars had already erupted between supporters of the conservative Simon Bolivar and the liberal General Francisco de Paula Santander in 1839. This violence would continue until 1885 when the Conservative Party took long-term control, the current Republic of Colombia was founded, and a new conservative constitution was put in place. Opposing ideas of the enlightenment, the Catholic Church was put in charge of the country’s education system.

Conservative Hegemony

The Conservative Party then ruled for 44 consecutive years in what’s been called the Conservative Hegemony.

During this period, Colombia lived relative low levels of political violence and conservatives can claim credit for constructing a nationwide rail system.

With the help of American economist Edwin Walter Kemmerer, the Conservative government of 1928 also created the country’s central bank that regulated the national economy and still operates today.

Nonetheless, the Conservative party also found itself deeply embroiled with accusations of chronic election tampering in its electoral battle with the liberals.

Article 1 of Law 61 (1888)

In order to administratively prevent and repress crimes and offenses against the state that affect public order, [the President] may impose — depending on the case, sentences of confinement, expulsion from territory, prison or the removal of political rights for the time deemed necessary.

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the so-called “Law 61” of 1888 enabled the president to prohibit any political activity which he considered a public liability. Liberal meetings were disbanded and “there was almost no Liberal newspaper that was not shut down.”

In 1886, less than 70 years after its independence, the Conservative Party approved Colombia’s 15th constitution in which Catholicism becomes the state religion and the Church is put in charge of the country’s public education.

Civil war re-surfaced as Liberal Party members attempted to regain control in 1899. This episode is known as the ‘Thousand Days War`. The aptly named three-year civil war did not result in Liberal victory but the population was successfully cowed into choosing a political side and the economy plummeted.

Another memorable scandal during this period of Conservative control was the 1928 Banana Massacre. Laborers employed by US company United Fruit Company participated in a month-long strike for ‘improved working conditions’. The government army forced sent to suppress the demonstration opened fire on a post-Mass congregation, killing between 300 and 3,000 people, including the wives and children of workers.

Political control since 1810

Liberals cease control

The violent repression, unrest among Colombia’s mostly poor population and an increasingly popular Liberal Party put the Conservatives under pressure. Due to internal divisions, the party ran two candidates in the 1930 election.

Receiving fewer votes than the two Conservative candidates combined but substantially more than either one of them, Liberal candidate Enrique Olaya took control of government in what is called the beginning of “The Liberal Republic,” during which the Liberal Party controlled both Congress and the Presidency.

Conservative Party leader Laureano Gomez was almost immediately appointed ambassador to Berlin where he was witness to the rise of Adolf Hitler and his National Socialism, something that would later reemerge on his return to Bogota when he and political allies tried to organize a repetition of the 1938 “Kristallnacht,” during which Nazi supporters in Germany coordinately assaulted Jews and Jewish property.

Meanwhile, in Bogota, the Liberals strengthened their control over the government. Following accusations of electoral fraud in the 1933 congressional elections and a no right to free election, the Conservative Party refused to take part in the 1934, 1938 and 1842 presidential elections, and the 1935 and 1937 congressional elections, leaving the conservatives out of Congress since it’s foundation.

Having no opposition, Liberal President Alfonso Lopez pushed through far-fetching constitutional amendments which included the right to citizenship for women, the right for workers to form unions, and the abolishment of Catholicism as state religion. Instead, Colombians were granted the freedom to religion, much to the discontent of the Catholic Church and the Conservative Party.

“The Violence”

Under the leadership of Gomez, the Conservatives regained control of the national government in 1946 when supporters of the moderate Gabriel Turbay and the more radical Jorge Eliecer Gaitan divided the Liberals. Conservative Party candidate Mariano Ospina became the third in his family to become president. Gomez became the foreign minister. The Liberal Party did maintain a majority in Congress.

As the government was locked between a Conservative government and a Liberal Congress, unrest grew in Colombia, particularly in the countryside where Colombians were increasingly unhappy by the almost oligarchical way the Liberal and Conservative elites were governing the country. Under the presidency of Ospina, Gaitan became immensely popular and his electoral support threatened the leadership of both the Conservative government and the Liberal Party.

The popular Liberal dissident was assassinated on April 9, 1948, a black day in the history of Colombia. His assassination spurred unprecedented violence; in the 10 hours after Gaitan’s death, thousands of residents of Bogota were killed in partisan riots. This violence spread across the country, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths in the eight years that followed.

As the country descended into all-consuming partisan violence, the Conservative Party remained in control of the government. Party president Gomez resigned as foreign minister and won early elections boycotted by the Liberals, who claimed the party was a victim of systematic assassinations by Conservatives.

According to historians, the conservative leader — and former admirer of European dictators Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini — was one of the most vociferous promoters of the partisan slaughter that was going on across the country. Gomez suspended the country’s courts and severely limited civilian rights and the press.

The Conservative president was not alone in inciting peasant followers against one another as Liberal leaders were equally fierce in waging the war against their political opponents. Self-defense guerrilla groups were formed in the countryside to defend themselves against hordes of armed men roaming the land to kill any member of opposing political views.

The Catholic Church, the Conservative Party’s ally since the 19th century, also actively took part in the mass killings. Father Fidel Blandon recounts in his book “What the heavens do not forgive” how several priests incited Mass congregations to assault political rivals violently.

In 1951, Gomez suffered a heart attack and was forced to step down. By 1953, the military ousted Gomez’ successor and installed the first dictatorship in the history of the republic. The controversial and now-unpopular Conservative leader was exiled to Spain.

National Front

Eight years and hundreds of thousands of violent deaths after the assassination of Gaitan, Liberal and Conservative leaders engaged in peace talks in Spain, where Gomez was residing, to control the carnage and restore democracy.

The political parties created the “National Front,” a bipartisan deal in which the Liberals and Conservatives agreed to rotate the presidency. While the pact had problematic implications for Colombian democracy, it did end the mass killings and normalized Colombia’s society.

The Conservative Party was granted to rule the 1962-1966 and the 1970-1974 terms, after which democracy was restored.

The end of the National Front also meant the end of the Conservative Party’s dominance over Colombia’s executive power. Since 1974, the party has only delivered two presidents; Belisario Betancur (1982-1986) and Andres Pastrana (1998 – 2002).

By the late 1980s, Colombia had sunk into chaos; guerrilla groups like the FARC, ELN, and the M-19 were making major territorial gains in the south of the country and carrying out large-scale attacks in the cities, while drug cartels like that of Pablo Escobar declared war on the state.

The most prominent Conservative victim of this violence was Alvaro Gomez, the son of the late Conservative leader.

The fiercest critic of the President Ernesto Samper (Liberal Party), controversial for his ties to the Cali Cartel, was shot and killed in 1995. Samper and senior Liberal Party executive Horacio Serpa were investigated for the homicide, but no culprit was ever established.

Colombian election results since 1931

The last Conservative President

The last Conservative president was Andres Pastrana (1998-2002), who initiated peace talks with the FARC in 1999. Support for these talks split the Liberal Party in two, while paramilitary factions promoted the creation of splinter parties.

By 2002, Colombia’s political scene changed entirely; The Liberal Party broke in two dissident factions, respectively led by Alvaro Uribe and Horacio Serpa. Paramilitary groups united under the AUC began actively infiltrating political parties to defend their criminal interests.

Uribe won the elections and invited the Conservatives to take part in his government. New political parties emerged, either with the support of dissident former Liberals or the AUC.

When the ties between the paramilitaries and politicians came to light in 2006, the Conservative Party was one of the hardest hit by the scandal. At least seven of the party’s congressmen were sentenced to prison.

By 2010, Colombia’s political scene had changed drastically, and the power of the Conservative Party and Liberal Party alike had diluted. Eight parties entered Congress, and the Conservatives received 21% of the votes.

The newly elected President, former Liberal Party mogul Juan Manuel Santos, invited the Conservatives to his “Coalition of National Unity,” but failed to grant important minister posts to conservative politicians.

In the meantime, prosecutors opened criminal investigations into the dealings of former Conservative Party ministers accused of corruption during the two terms of Uribe.