Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro has implied he may end efforts to negotiate the dismantling of paramilitary organization AGC, which could threaten his “Total Peace” policy.

Petro ordered the security forces to end attacks against the AGC, a.k.a. “Clan del Golfo,” on January 1 in order to facilitate negotiations with one of Colombia’s most powerful illegal armed groups.

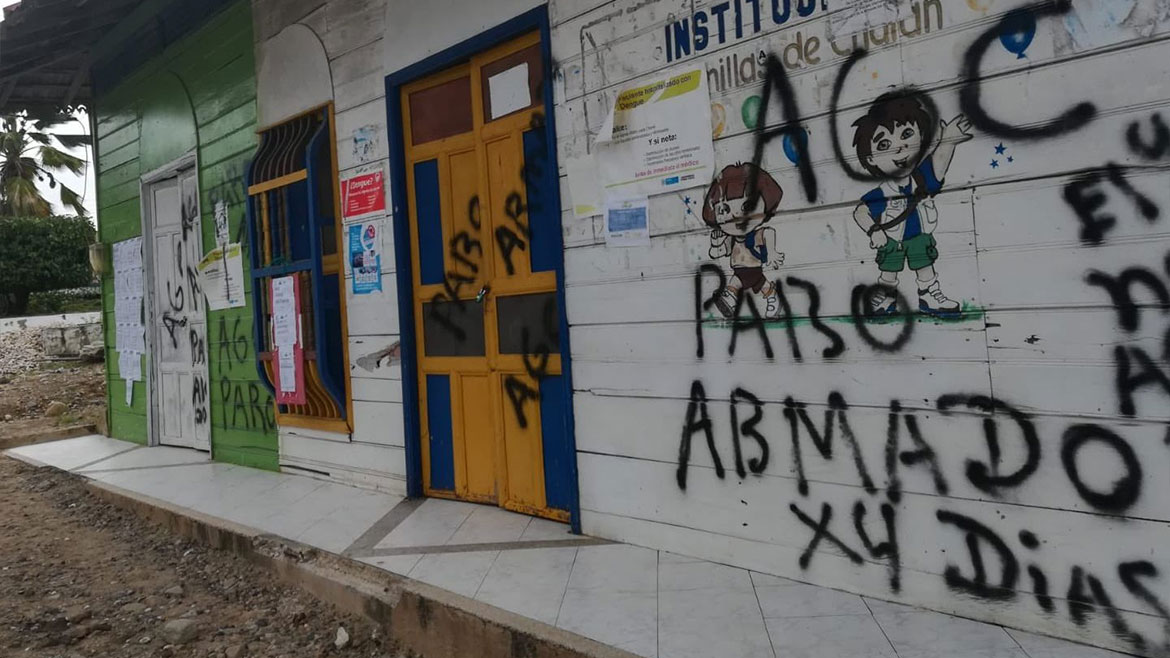

Prosecutor General Francisco Barbosa has refused to lift paramilitary leaders’ arrest warrants that would allow talks, however, and Petro said Sunday that the AGC “has broken the ceasefire” during violent miners’ protests in the north of the country.

In a press conference, Petro warned illegal armed groups “not to deceive the government and to “clearly understand” that his peace policy seeks “to dismantle drug trafficking and illegal mining.”

Colombia’s ‘total war’ on illegal mining shuts down gold mining region

The politics of the paramilitaries

The AGC agreed in 2017 to negotiate this with former President Juan Manuel Santos already and declared a unilateral ceasefire in August last year to show that they were serious about Petro’s Total Peace plan.

Following Barbosa’s refusal to grant the government’s request to lift AGC leaders’ arrest warrants, the paramilitaries’ top commanders hired defense attorney Ricardo Giraldo, who told media that the the AGC wants the government to recognize “political character,” which would allow them to take part in a peace process.

They have always been attacked as criminal gangs, but if you don’t know the context it is very difficult to understand the conflict.

AGC attorney Ricardo Giraldo

Meanwhile, the Ombudsman’s Office issues two alerts since December about the “territorial expansion and the consolidation of control of the AGC or the Clan del Golfo in urban centers and the countryside” in multiple parts of Colombia.

Think tank Paz y Reconciliation (Pares) told newspaper El Espectador additionally that the AGC has intensified the intimidation of locals in regions under their control and in some parts of Colombia have become “the biggest employer in the region.”

While government authorities claim that the AGC consists of no more than 3,200 members, Giraldo told media that the AGC’s payroll has grown to 9,000 people and “provides assistance to communities the government’s won’t.”

Local elections in Colombia: candidates giving away drugs for votes

Same as always

Colombia’s and US authorities have been downplaying paramilitary organizations’ access to dirty money to expand their associates’ political power since 1974 and continue to do so.

According to the Truth Commission, the partial demobilization of the AGC’s predecessor, failed to properly investigate the regional elites that used the AUC’s drug money to grow their political power.

Consequently, these elites continue to threaten democracy, this time with the help of the AGC and similar paramilitary and organized crime organizations, according to electoral observers.

A report released by Pares earlier this month, revealed that these paramilitary networks also pose a threat for the local and regional elections set for October.

{political-electoral violence} is linked not only to local dynamics of armed conflict and criminality, but also to clientelistic and corrupt political dynamics. Traditionally, violence has been and is used as another mechanism of electoral competition. In the case of local and departmental elections, there are sophisticated corruption mechanisms that include diverse alliances with all types of organized armed groups.

Paz y Reconciliacion

The ongoing refusal to recognize the AGC’s involvement in politics may not just pose a threat to the upcoming elections, but could perpetuate the use of paramilitary groups for political purposes.