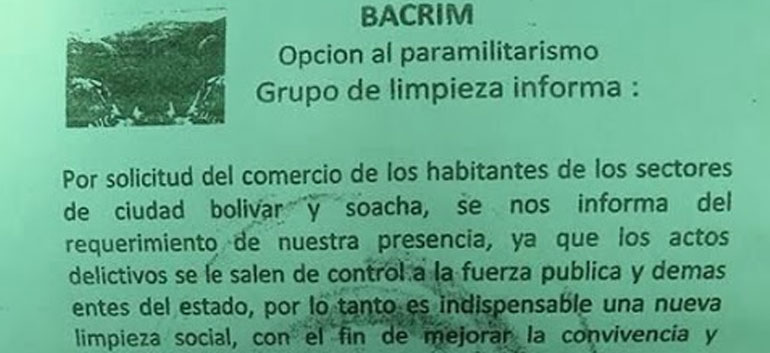

An unknown group in Bogota has distributed a pamphlet announcing its intentions to engage in “social cleaning” activities in one of the Colombian capital’s poorer neighborhoods, national media reported Wednesday. Distributed on January 24, the pamphlet was posted on the streets of Bogota’s Ciudad Bolivar, a poverty-stricken neighborhood on the outskirts of the city inhabited by over half a million people. This just two weeks after a similar flyer made its way around Medellin, Colombia’s second largest city.

MORE: Announced Medellin ‘social cleansing’ undermines democracy: security expert

The Bogota group claimed to be acting on behalf of the neighborhood’s inhabitants and commercial sector, stating that “crime is no longer under the control of the public force or the state, that’s why new actions of social cleansing are indispensable in order to improve coexistence and security.”

The group imposed an 11PM curfew for the next month, explicitly threatening criminals, gay individuals and specific establishments like bars, night clubs and brothels. A so-called “black list” with names of persons who would “disturb the peace within the community” will also be targeted, according to the flyer.

According to El Espectador newspaper, some have since suggested that the group could be responsible for four homicides that took place in the neighborhood since the flyer was distributed. Authorities have rejected those claims, however, stressing that the homicides in question were “isolated cases” that had nothing to do with the announcement.

Since the beginning of January, 14 homicides have occurred in the crime-ridden Ciudad Bilovar neighborhood, where violence is typically high.

Bogota Mayor Gustavo Petro stated that “the Mayor’s Office cannot allow this, if we have to ‘go back’ into Ciudad Bolivar, we will do that day and night,” referring to a recent policy initiative strengthening the police and military presence in the neighborhood.

“We have spoken to the Minister of Defense about this situation, and I publicly announced before that there are organizations trying to establish territorial control. We cannot allow the Bogota youth to murder. A country that allows its youth to murder does not deserve to be called a country,” the mayor was quoted as saying by El Espectador.

With the threat of social cleansing looming over Colombia’s two largest cities, the longtime issue of armed extra-judicial “defense” groups exercising arbitrary law has resurfaced on a large scale.

Security researcher Heidy Gomez of the Observation Center of Human Security (OSHM) told Colombia Reports in a previous interview even so-called “justified acts of force on behalf of ‘good citizens’” are a subversion of democracy and the state’s jurisdiction over the use of deadly force.

Former Medellin Peace Adviser Luis Guillermo Pardo attributed the development of these groups in part to a “lack of public authority in the city and the rise of street crime and insecurity.”

Colombia has a long and bloody history of social cleansing, carried out by illegal and semi-official armed groups from different political orientations. The tactic was first employed in urban areas by so-called “self-defense groups” in the 1970s.

Right-wing paramilitary organizations and left-wing militias later adopted the strategy throughout the armed conflict of the 1980s and 1990s as a means of filling a void in state authority and weeding out enemy factions and sympathizers.

Under the guise of ensuring public safety, social cleansing has been responsible for innumerable human rights violations in the country’s urban and rural areas including displacement, rape and murder. Homeless populations are particularly affected in cities, while in the countryside the tactic is typically used as a cover for politically motivated killings and labor suppression.

Sources

- Crecen alertas por panfletos de ‘limpieza social’ en Ciudad Bolívar (El Espectador)

- Panfletos en Ciudad Bolívar y Soacha (El Espectador)

- Policía dice que asesinatos en Ciudad Bolívar no tienen relación con panfletos amenazantes (El Espectador)

- Interview with Heidy Gomez