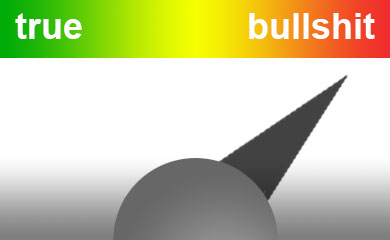

Colombia’s President Duque insisted Monday that “evidence and results” show he is implementing the peace policies agreed upon in 2016, so we had a look at the evidence and results.

The peace process obligated the government to implement five points that make it easy to measure whether the president is telling the truth or misinforming the international community.

Comprehensive rural reform

As part of the peace agreement, the Colombian state agreed to a comprehensive rural reform that would help landless farmers obtain land rights. So far, the Duque administration has made no proposal in this regard whatsoever.

As part of the peace agreement, the Colombian state agreed to a comprehensive rural reform that would help landless farmers obtain land rights. So far, the Duque administration has made no proposal in this regard whatsoever.

In fact, the government’s National Development Plan for rural areas is based on three pillars; industrial agriculture, mining and lumbering, economic activities that have previously only contributed to the aggravation of land inequality in Colombia, one of the leading causes of the armed conflict in Colombia.

Back in April, the National Land Agency announced “one of the largest granting of property titles”, consisting of 123 land titles to small farmers out of 1,300 land titles planned to be granted this year. This stands in no comparison to the year before Duque came into force when thousands of such titles were granted.

The Kroc institute, which measures progress of the implementation of the peace process, registered no progress related to the land reform agreement since Duque took office in August last year.

Understanding the causes of Colombia’s conflict: land ownership

Increased political participation

The peace process also sought to strengthen opposition’s rights and the right to protest. Most importantly, the peace deal promised to add 16 seats to Congress for representatives of 16 long-neglected and war-torn areas.

The peace process also sought to strengthen opposition’s rights and the right to protest. Most importantly, the peace deal promised to add 16 seats to Congress for representatives of 16 long-neglected and war-torn areas.

Duque’s party has opposed this, claiming that the seats for the victims from conflict areas would be “seats for the FARC.”

Colombia’s former Interior Minister is now trying to collect more than a million signatures to force the State Council to finally decide on a 2017 petition to overrule a controversial decision by former Senate President Efrain Cepeda (Conservative Party) to reject a senate vote that granted the seats.

Despite this, the Kroc Institute registered ongoing progress in the implementation of this point, but also pointed out that the implementation of almost 50% of the agreements have not even begun.

Comprehensive approach to drug problem

Colombia’s peace deal included a new drug policy that allowed farmers dependent on coca harvests to receive government aid to plant alternative crops if they voluntarily removed their coca stocks.

Colombia’s peace deal included a new drug policy that allowed farmers dependent on coca harvests to receive government aid to plant alternative crops if they voluntarily removed their coca stocks.

In April, almost 130,000 families had registered to take part in this plan that would also see investment in the creation of road infrastructure that would allow the farmers access to the legal economy.

Duque never included the $488 million necessary to execute this policy in his 2019 budget. Consequently, many farmers who have removed their coca crops now find themselves devoid of al livelihood. Some have said their families are literally starving while others admitted they saw no other option than to return to growing coca.

To complicate the situation even more, Defense Minister Guillermo Botero, who initially said he would scrap the program, has ordered forcibly eradicating the coca stocks of families who subscribed to the so-called PNIS program and has failed to provide security to the community leaders who are threatened by drug trafficking groups.

This hard-line approach has never worked, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and is still not working. Coca cultivation in 2018 increased to record heights.

The Kroc institute registered a general stagnation of the execution of this part of the peace deal since Duque took office.

Transitional justice

The peace deal saw the creation of a transitional justice system that would seek justice to the greatest possible extent for the country’s 8.5 million conflict victims. The ordinary justice system could never adequately provide justice simply because of the sheer volume of victims. To illustrate, it would take more than 16 years just to listen to each victim for one minute.

The peace deal saw the creation of a transitional justice system that would seek justice to the greatest possible extent for the country’s 8.5 million conflict victims. The ordinary justice system could never adequately provide justice simply because of the sheer volume of victims. To illustrate, it would take more than 16 years just to listen to each victim for one minute.

The Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) that was agreed between the warring parties and victims has been actively opposed by the president, who refused to sign off on the statutory law that would define the court’s powers.

Duque severely cut the budgets for the truth commission that seeks to clarify the mass victimization and the prosecution unit that hopes to return the remains of some 120,000 missing persons.

Victim reparation

In regards to victim reparation, Duque’s far-right Democratic Center party has been seeking an amendment of the 2011 Victims and Land Restitution Law that would make it virtually impossible for victims of displacement whose land has been dispossessed to reclaim their land.

In regards to victim reparation, Duque’s far-right Democratic Center party has been seeking an amendment of the 2011 Victims and Land Restitution Law that would make it virtually impossible for victims of displacement whose land has been dispossessed to reclaim their land.

Duque’s National Development plan seeks reparations for 471,000 victims. This is 282,000 less than those who received reparations under former President Juan Manuel Santos. In regards to land restitution, Duque limited the possibility of displaced persons to register the dispossession of their land.

Furthermore, Duque appointed controversial former palm oil federation chief Jaime Castro in charge of land restitution. Castro represented multiple palm oil companies who were criminally charged for dispossessing land from small farmers with the help of paramilitary death squads and the military.

It is unclear how many lands were effectively returned under Castro.

Disregarding the previous controversies, the Kroc Institute registered a continuation of progress in the implementation of previously initiated victims agreements, but noted a stagnation in the implementation of 45% of agreements that were never initiated.

End of conflict

The end of conflict chapter of the peace deal was largely about the FARC’s demobilization, disarmament and reintegration.

The end of conflict chapter of the peace deal was largely about the FARC’s demobilization, disarmament and reintegration.

In London, Duque told press that “you have seen what the stance has been” in regards to the reintegration of former FARC fighters and invited the public to look at the “evidence and results.”

The results are absolutely disastrous. Duque’s ongoing resistance to the country’s war crimes tribunal has created major judicial insecurity among guerrillas. In December, 3,000 demobilized guerrillas were still in their reintegration camps. Earlier this month, only 1,700 have left.

Furthermore, Duque ended peace talks with ELN guerrillas, which could have put an end to the victimization of civilians as a consequence of the armed conflict that began in 1964, once and for all.

Also in this part of the peace agreement, the Kroc institute registered an almost total stagnation since Duque took office. In fact, some agreements appeared to have been rolled back while Duque was in office.