Colombia’s comptroller general said Wednesday that watchdog entities found evidence that $20 million (COP80,000million) meant to confront the coronavirus pandemic has been embezzled.

In an interview with RCN Radio, Comptroller General Carlos Felipe Cordoba said that his office, the prosecution and the Inspector General’s Office found irregularities in some of the 37,000 contracts that have been granted to combat the crisis.

The irregularities would have taken place in the two weeks after President Ivan Duque announced major investments in healthcare and poverty prevention.

Let’s steal from the poor!

Cordoba found, among other things, “inflated costs in contracts signed by mayors and governors in different areas of the country, which we are monitoring to prevent them from making a killing of such a pandemic.”

The comptroller general said that the governor’s office in northeastern Arauca province was deducting cans of tuna at the price of $4,85 (COP19,000) and bars of soap at the price of $8,45 (COP33,000).

Governors’ offices and municipalities are signing contracts that generate suspicion because of irregular values and for not having the necessary information about the contractor.

Comptroller General Carlos Felipe Cordoba

Inspector General Fernando Carrillo told the radio station that his office so far received complaints about corruption in the awarding of emergency contracts in five provinces, two municipalities and one hospital.

Carrillo was particularly indignant about the embezzlement of funds meant to prevent hunger while a quarantine is in place to slow down the spread of the virus in Colombia.

It’s an outrage. This is using the hunger of the most vulnerable and turning them into the banquet of the most corrupt.

Inspector General Fernando Carrillo

Citizens call fraud in Bogota too

While the watchdogs highlighted corruption on the provincial and municipal level, citizens were reporting irregularities in the granting of emergency funds to poor families by the national government.

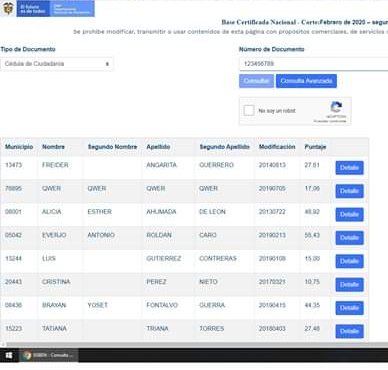

The National Planning Department, for example, was accused of fraud after citizens found it had granted emergency stipends of $41 (COP160,000) to non-existent people.

The ID card number 123456789 had been granted 49 of these stipends with a total value of $2,000, one vigilant citizen saw on the platform before it was closed because “there was an anomaly that is being overcome.”

Corruption in the granting of government contracts is normal in Colombia, but particularly problematic because the enormous funds released to deal with the emergency can’t be checked as easily as usual.