Colombia will vote in an October 2 plebiscite held to gauge popular sentiment concerning the peace accords recently finalized between the Colombian Government and the guerrilla group FARC. The country’s main labor unions support the deal.

The signing and the expected electoral approval of the peace agreements would bring to an end the armed conflict waged between the FARC, the Colombian Government and numerous paramilitary factions which has caused more than 267,000 violent deaths as well as millions of victims, making Colombia the country with the second highest number of internally displaced people in the world, over 7 million.

Indeed, this peace deal, negotiated over the past four years in the city of Havana, Cuba, would culminate in the transition of the FARC from an armed insurgency group, formed 52 years ago, into a political party accorded minor congressional representation.

Such a deal, brokered during four years of intense negotiations, covers six chapters and marks a novel attempt to seriously incorporate a platform for justice and victims within the more concrete process of ensuring that the insurgent armed group makes the transition from military-guerrilla struggle to electoral politics.

The chapter on victims and its relation to justice seeks to uphold three core elements, via a form of transitional justice based on truth, reparation and no repetition.

Herein, for all those who openly and completely profess their crimes, they will be accorded a form of non-incarcerated punishment which will involve both territorial seclusion and community-focused reparation-type work. All other perpetrators of crimes against humanity who do not voluntarily confess will face jail time of between 15 and 20 years.

This model of justice moves beyond a Kantian and Hegelian understanding of punishment as retribution towards a Hobbesian understanding wherein any form of penance should focus on the reformation and education of the guilty party.

The Colombian union movement has, like many other social movements, suffered enormously during this decades´-long conflict.

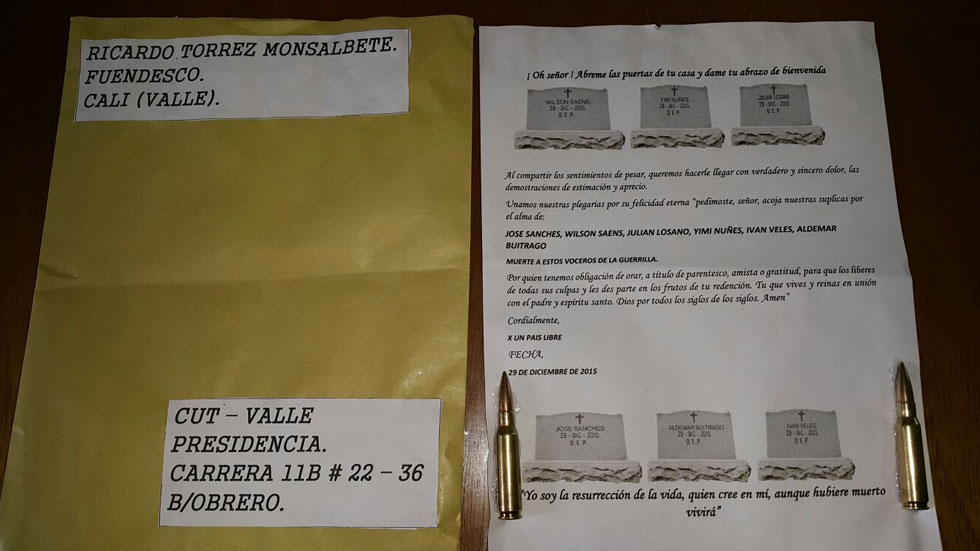

The database of the National Union School of Colombia (ENS) paints a torrid picture of the woes bestowed upon Colombia’s unionists: from 1986, the year marking the creation of the country’s largest union confederation (the CUT) until August 26, 2016 (the date of the formal end of the peace negotiations), 14,103 violations have been recorded against this population, including 3,043 murders, 6,872 death threats and 1,895 forced displacements.

Although the FARC has not been one of the major perpetrators of anti-unionist violence, being responsible for an estimated 3% of all violations (432 in total), as opposed to 24% for paramilitary groups, 7% for State organisms and over 64% unaccounted for, without doubt the existence of the guerrilla-State conflict has markedly and historically exacerbated both anti-union violence and anti-union business and State practices.

The weak and fragmented nature of Colombian unions underlines this point. Union density, for 2014, came to only 4.5% of the workforce and over 80% of Colombian unions have less than 100 members, a factor which severely limits their bargaining leverage.

Indeed, a recent study by the ENS showed that only 0.3% of all formally-registered Colombian businesses had signed a form of collective bargaining agreement, a fact that demonstrates the extremely precarious nature of social dialogue in the realm of labor relations.

The peace agreements, as such, offer a new beginning for the Colombian labor and social movements as a whole.

For decades workplace and broader socio-political and land-based struggles have been tinged with the tag of being sympathetic, if not openly in collusion with, the FARC and other guerrilla groups.

Branches of the Colombian government have even been found to have had directly conspired with far-right paramilitary factions as a means of threatening and murdering unionists who were deemed as being thorns in the side of the Colombian State.

For instance, in 2011, Jorge Noguera, the former director of the former state intelligence agency DAS, was sentenced to 25 years in prison for the crime of criminal association with paramilitaries that resulted in the murder of, at least, seven union leaders.

And while anti-union violence and persecution has decreased significantly since the end of the far right-wing presidency of Alvaro Uribe in 2010, there were still 130 unionists killed between 2011-2015, even after President Juan Manuel Santos signed a Labor Action Plan with his US counterpart Barack Obama as a means of ending union persecution and improving the Colombian government’s protection of fundamental labor rights.

Without doubt the possibility of broadening union freedoms and the avenues open to peaceful social protest become much stronger in a context where war no longer exists.

It is for this reason that the vast majority of Colombia’s union leadership is actively supporting the peace process and, especially, the Yes campaign for the plebiscite that will determine whether or not the Agreements receive the required electoral support.

The CUT, the teachers’ union, Fecode (the largest union federation in the country) and the petrol-workers’ union (USO), are all currently conducting nationwide workshops, in alliance with diverse NGOs, which are geared at both informing union members and the wider community of the content of the agreements as well as discussing how the Colombian union movement can both grow in size and influence in a context in which the FARC have laid its arms to rest.

Author Daniel Hawkins is the Director of Research of the National Union School of Colombia (ENS)