Hugo George is one of the hundreds of social leaders who have been murdered in Colombia during its peace process. He was also my friend.

I met Hugo on a beautiful afternoon in late October of 2017 on his beloved 800-hectare farm of Manzanares located just outside of the mountain village of El Aro in the municipality of Ituango, Antioquia.

Immediately, I was struck by the love and care with which he and his seven siblings treated the land they lived on. A proud “campesino,” Hugo wore his signature “vueltiao” hat and the large sunburns that covered his arms and face as a badge of honor—a symptom of hard work and long days in the sun—all needed to provide for his extensive family of eleven children and one grandchild.

And like many relationships, ours began over a meal. While seated at his brother Humberto’s dining table overlooking the Cauca River eating a plate of rice and “chicharrón,”

Hugo gave me a heartbreaking account of how he had managed to survive the world’s longest war, an account I would never forget. Not once did it ever occur to me that six months later he would become one of 500 community leaders killed since Colombia signed its landmark peace deal with FARC in November of 2016.

The peace deal was supposed to put an end to a five-decade conflict that took at least 260,000 lives, displaced 7.4 million people (15% of its population), and ravaged the Colombian countryside. But what Hugo and Hugo’s death taught me was that no piece of paper could eliminate the profound unequal distribution of land and wealth that pushes countless of poor Colombians, both urban and rural, into the frontlines and into the drug economy.

Understanding the causes of Colombia’s conflict: land ownership

Although FARC, the country’s largest rebel group, had been founded to combat the most unequal distribution of land in Latin America, out of temptation and necessity the group had turned to the cocaine trade to fund its insurgency. With drug profits and criminality added into the fold, what began as an ideological war over property rights also became a drug war over market share, and thus one of the most complex and enduring conflicts on the planet.

None of this was apparent when I first walked into the region of El Aro, one of the regions most devastated by the fight for land and drug profits. I will never forget my awe at the plentiful guava and mango trees, the sound of streams flowing from the mountainside, and the endless supply of colorful butterflies soaring above.

The scenery, was a more than worthwhile reward after a grueling eight-hour ascent from the riverside town of Puerto Valdivia via dirt roads slashed into the Andes Mountains on foot and on muleback.

But its undeniable beauty existed alongside coca leaves and cocaine labs peppered across the landscape, all hints of a history of violence and loss that is forever seared into my memory and into the memories of the people, like Hugo, who survived it.

The presence of coca and cocaine, lay bare a wound in a land that still bled twenty years after the very community that once sustained it was virtually wiped from the map.

The massacre in El Aro

It was no coincidence that I was in El Aro in the last week of October of 2017. As a journalist, I was there to cover the 20th anniversary of the El Aro Massacre, a week-long seek siege carried out by right-wing paramilitary groups belonging to the AUC or United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia in 1997.

The massacre was part of a broader counterinsurgency waged by right-wing vigilante groups in FARC controlled territory during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Allied with Colombian elites, the paramilitary groups, nearly eliminated the rebel group and challenged its control of the drug trade.

But FARC and the American appetite for drugs proved far more resilient than the paramilitaries and the state who abetted them could have ever imagined. The war continued, but El Aro barely survived, as the paramilitaries burned the town to the ground once the bloodshed had ended.

It was simply not enough for the paramilitaries to murder 15 civilians who they wrongfully accused of being accomplices of FARC in the town square in front of everyone who knew them. Nor was it enough for the paramilitaries to displace over a thousand local farmers and to force them to watch as they stole their livestock.

FARC’s sworn enemy came with one goal in mind, to destroy. But once their reign of terror was over and the smoke dissipated, some of El Aro’s son and daughters, Hugo among them, embarked on a quiet revolt. They returned. And they began the long process of making something out of the rubble. It was not an easy choice or an easy life. But it was all they knew. El Aro, however, was unknowable.

20 years on, El Aro’s once colorful adobe homes were still charred by fire and its streets were hauntingly empty. The church, the only original building that still stood, was hollow, as there were no longer enough people to justify having a parish. The town, although partially rebuilt, looked more like a monument to the past than a place for people to live in.

Only 42 families lived in the village proper compared to the 300 who once called it home. By then the communities that had once depended on trade with El Aro for their livelihood had either disappeared or turned to the drug trade to survive. History had forgotten El Aro, but those who survived the massacre had not.

Hugo had not been to El Aro in years when we met outside of the community he used to visit on a weekly basis to sell crops and livestock. In fact, it was his dependence on the community that put him in the community when the massacre began on October 25, 1997. He was in town to sell a drove of pigs he had fattened to his family friend Marco Aurelio Areiza when he first heard the gunshots on that fateful Saturday morning.

Over the bloody week, he saw over a dozen people he knew murdered indiscriminately, Areiza among them. In Hugo’s eyes, their deaths were the product of having lived in enemy territory; a circumstance they could not control. “The paramilitaries said that anyone who had cooperated with the guerrilla or who had talked to them was a guerrilla,” he told me exasperatedly.

His tone was rare for a man known for his calm, often joking demeanor, but whose harrowing memories of the massacre brought out a pain and a hurt that time could not heal.

They couldn’t understand that when an armed person approaches you and asks you a question, you answer it. They unjustly accused the victims of being collaborators of the guerrilla. But they were just trying to live. That is how we all lived.

Hugo George

FARC returns

His words would prove to be especially resonant, as on October 28, 2017, the day after our first meeting, two-decades to the day of the massacre, FARC returned to the region.

Hugo was forced to confront its rearmed members once again, in yet a new phase of the Colombian conflict that the world had said was over, but had only shape-shifted.

The rearmed guerrilla members had come to collect his son-in law who had taken on a side job as a middle man selling cocaine to resurgent paramilitary groups who had reemerged in the region in light of the power vacuum left by FARC’s alleged demobilization.

But for low-ranking FARC members, territory and the cocaine produced inside of it were not easy to give up, especially when the promises and possibilities established in what was supposed to be a revolutionary peace process remained elusive.

The two men who showed up at Hugo’s doorstep came hungry for the security that only drug profits could bring and for the head of a man who they believed was betraying their right to that security. And when they saw his son-in-law get out of bed to begin his day, the dissident guerrillas surrounded him with two revolvers, ready to shoot.

He proved far more agile than they could have imagined, and began sprinting down the mountain towards the Cauca River as the dissident members shot at him repeatedly. All of the while, Hugo watched from his dining table where he was sorting good beans he had just harvested from the bad. He did this, as he followed the unspoken rule of this land, he saw, but he did not act. The machete strapped at his waist side was no match for their guns.

The men returned a couple of hours later, empty-handed, but with a warning. “We are anti-paramilitaries,” they told him. “We are former members of the 36th front of FARC and we want you to know that anyone who sides with the paramilitaries will be killed. We know that you are an honest, hardworking man. But if you get involved with those people, you will pay.”

In retaliation for his son-in-law’s betrayal, the men took his two most important assets, assets he had saved for years to buy, his mules. And in doing so, they took his only form of transportation in a region characterized by rough terrain and long distances.

This time, he said what he did not say during the massacre. “We aren’t on anyone’s side,” he told them. “All we have done is suffer at your hands. We are hardworking, honest people. We are campesinos that is all we are.”

The guerrillas didn’t listen and shot a bullet into the air before they rode off with his mules, as Hugo looked on, powerless.

No explanation was needed, as in a land defined by blood and destitution, compassion is a lot harder to shoot than a bullet.

I did not hear the bullets that were fired that day. I was an hour walk away sleeping at his brother Humberto’s house who was hosting me. But I did hear Hugo’s recollection of the events, as he ran over to tell me and Humberto what had happened.

I will never forget the urgency and fear in his voice, he was breaking the very thing that had kept him alive in a place where 50 is considered old, his silence.

After the flood: How the Hidroituango crisis changed armed group dynamics in northern Colombia

Hugo’s death

Until May 2nd, 2018, I did not fully understand the significance of the words that came out of Hugo’s mouth. On that day, I received a Whatsapp message with an image of his lifeless body and his signature vueltiao hat blasted from his head, killed by the same violence he had spent 48 years outmaneuvering.

It was in that moment when I knew that Hugo was the most courageous person I had ever met and that I was determined to know the causes of his death. I started off by turning to the Colombian media.

The local press reports all said the same thing. The story went that he was shot at 11 am on May 2nd by an unknown gunmen while he was sitting at a café in Puerto Valdivia with his nephew Dimar Ejidio Zapata, who also died in the shooting.

They said he was in town to attend a protest led by Rios Vivos, an activist group of which he was a member. The protest was against the $4 billion Hidroituango dam 38 km upstream, built by EPM one of Colombia’s largest multinationals.

Rios Vivos is well-known in Colombia for its stance against a dam that since construction began in 2011 has caused irrevocable humanitarian and environmental damage to one of the region’s most affected by the Colombian conflict. As such, Rios Vivos members have been subject to frequent threats, and even assassinations, not just for their position against Hidroituango, but also for their work protecting the rights of the local farmers.

Most of those actions have been allegedly executed by right-wing paramilitary groups that were not signatories to the 2016 peace agreement and who have a history of targeting all forms of activism viewing it as a product of left-wing ideology.

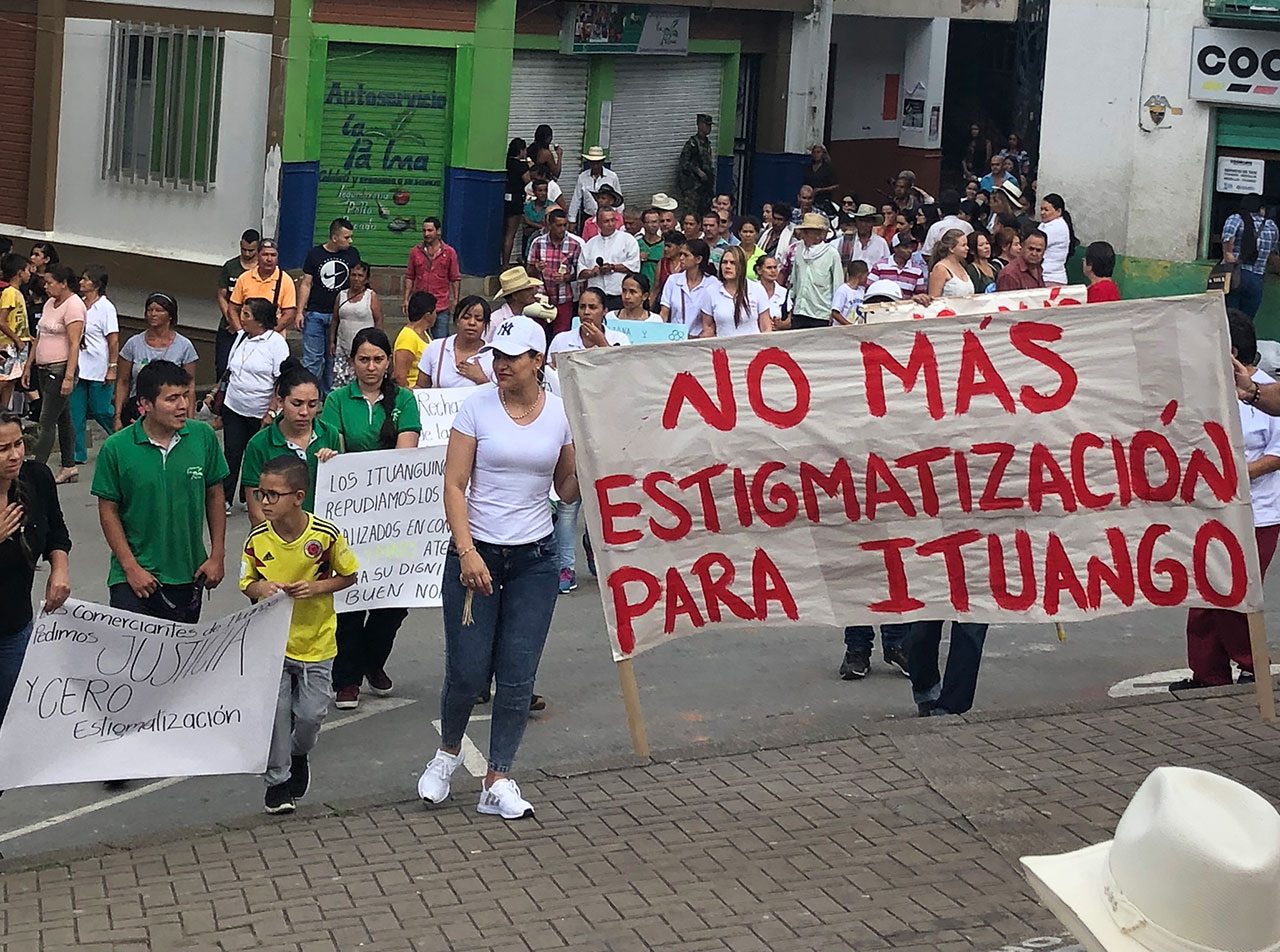

Thus, when Hugo was killed, Rios Vivos immediately claimed his death as a tragic product of the violence and risks faced by its members. This claim only grew in intensity, the moment that Puerto Valdivia suffered catastrophic floods caused by technical failures at the dam site just 10 days after Hugo’s assassination—and his assassination became an international news story meriting coverage from The Los Angeles Times and the BBC.

Two more social leaders murdered as EPM rushes to inaugurate hydroelectric dam

The floods did more than damage Puerto Valdivia’s economy, they also erased the true causes of Hugo’s death.

I soon found that the outrage over the killing of human rights activists was part of a larger Colombian tradition, the tradition of using political differences and the drug-trade to cover up for the violence created by one of the world’s most inequitable land tenure systems.

And it was out of a sense of conviction and responsibility to Hugo that I returned to Colombia in November of 2018 to pay my condolences to his family and to report on his death. To do this, I decided to meet up with the person who knew him best, his brother Humberto.

We elected to meet in the town of Ituango, the namesake of the Hidroituango dam and closest town to El Aro outside of Puerto Valdivia, a place, Humberto, had sworn he would never return to. He was eager to be interviewed and to explain what he believed was the true cause of his brother’s death—a land dispute over Manzanares.

The land dispute

“The reports he was in Puerto Valdivia for the protest were a lie,” Humberto told me as we sat in the town’s main square across from a group of soldiers patrolling the quaint town’s streets—a legacy of the municipality’s identity as one of focal points of the conflict.

“Hugo rarely left Manzanares, but he had to leave for a doctor’s appointment. And on the way back he stopped in Puerto Valdivia to visit my mother. Hours later he was dead. Everyone said it was because of the threats Rios Vivos members receive, but we have been receiving threats for years.”

Like many small farmers in Colombia, the George family live on Manzanares informally as they do not have titles to the land, despite having lived there for over fifty years.

In a country where, according to Oxfam, two-thirds of agricultural land is concentrated in just 0.4 percent of landholdings, informality and weak land rights are a fact of life. So much so, that according to the Land Formalization Project under the Ministry of Agriculture, 48% of the 3.7 million rural parcels contained in the National Cadastre do not have registered titles.

The instability of land claims and the absence of the rule of law has made families like the George family vulnerable to forced displacement at the hands of armed groups and multinationals willing to expel poor campesinos from their land in the name of profit, with drug profits receiving the most attention.

As a consequence, Colombia boasts one of the highest rates of internal displacement in the world, surpassed only by Syria. Hugo was doing everything in his power to prevent his family from being yet another statistic.

For decades the George family has received threats from individuals jealous over their claims over Manzanares, a property they came to live on after their father was hired as an administrator by the longtime owner, Jesus Londoño. They were content living as the caretakers of the property, until Londoño was murdered in a duel over thirty years ago.

He left no direct heir, and the woman who inherited the property, abandoned it. With no one alive to remember a life elsewhere and with no one coming to claim the land, the George family stayed on Manzanares. But in doing so, they caught the attention of their neighbors, many of them extended family, who wanted and continue to want a slice of the extensive estate.

Over the years, the George family has suffered intense harassment and intimidation by those jealous over their claim to Manzanares, but they have never wavered, believing that the land is rightfully theirs.

As the designated leaders of the family, Hugo and Humberto dutifully attended every meeting convened by armed groups on behalf of their challengers to settle the dispute. But the armed groups, regardless of their political affiliation, always sided with Hugo and Humberto, leading to more envy and rancor among their neighbors.

Their resentment only grew when in late 2018 Hugo decided to join Rios Vivos, mainly because of his opposition to the dam below, but also for its strong legal apparatus that could help him finally formalize his family’s land claim after years of obstruction by corrupt lawyers and an indifferent state.

Fears that Hugo would succeed, ultimately resulted in someone paying a local assassin in Puerto Valdivia $600 (COP1.8 million) for his murder, a murder that happened to take place on the day of a Rios Vivos protest he had no plans of attending.

The significance

Coincidence and timing made Hugo’s assassination into an unintended and misplaced rallying cry for the murder of human rights advocates in a post-conflict Colombia. And despite its false symbolism, Hugo’s death still has a lot to say.

On one hand, it tells us that being a peasant in Colombia has always been and remains deadly. More significantly, however, it tells us that if Colombia is to achieve true peace, it has to work for it by addressing the roots causes of the conflict—land and who has a right to claim it.

Mobilizing an effort to formalize the land claims of the millions of its citizen who own land, but who lack the paperwork to prove it, is a start. But peace will also require a change in attitude.

Until Colombia centers its most vulnerable people at the center of its political and economic system, farmers like Hugo will continue to die in ways that seem unavoidable, but are really the outcome of government apathy and inaction.

Yet amidst the bodies that will inevitably pile up there will be people like him who will continue to tell their truth—that the land belongs to those who work it—regardless of the risks. And it’s that truth that Hugo’s family is keeping alive.

Despite the ongoing threats against them, led by Humberto, the George family still lives on Manzanares, preferring to die than to give up the idea that Hugo died fighting for.

However, there is one thing that has made Humberto reconsider. “I won’t to lie to you, I have hatred towards the people I believe who killed my brother” Humberto told me, his eyes full of a sadness and a pain that could only belong to a man whose entire world had been taken away from him.

I will tell you one thing if that hatred ever made me think of seeking revenge that would be the moment that I would abandon Manzanares forever. Like Hugo, I just don’t have it in me to do evil to others.

Humberto George

It was hearing Humberto’s words, when I realized that Hugo’s story, was more than a story about the human cost of the Colombian conflict.

It was also a story about hope, about doing what is right in a place where it is so easy to do wrong, and about the extraordinary courage ordinary Colombians carry in a country governed only by uncertainty.

That possibly, the only remedy to that uncertainty, to the ruthless uprooting of lives and dreams, is integrity, as that may be the only thing that cannot be displaced.

Perhaps, the only path forward for a peaceful Colombia is adopting Hugo’s conviction, the insistence on doing what needs to be done, rather than what is most comfortable.