After 52-years of war and four years of negotiations, the Colombian government and Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia (FARC) have reached a final peace agreement. Colombians will have the final voice in a plebiscite as to whether or not the peace accords are implemented, but where is the voice of the youth? While those under 18 years old won’t vote in the plebiscite, they have voices and opinions that are worth hearing.

On the radio, in newspapers and magazines, throughout towns and cities, with a coffee, beer, or agua de panela, Colombian citizens are ardently discussing the peace accords with the FARC. The impending vote on the agreement appears to have taken the country by storm.

Polls that are published almost daily regarding the vote indicate that public opinion is in flux and that there are many who are unsure whether they will ultimately vote “Yes” or “No” in the plebiscite on October 2nd. Although none of the polls have surveyed minors under the age of 18, youth in high school classrooms throughout Bogota are debating the issues with energy and passion.

In one high school, for example, in the “Las Colinas” neighborhood, teachers organized a debate on the peace accords for the students. The vast majority of students supported a “No” vote, rejecting the accords, while three students abstained.

According to the students, there wasn’t enough information or diversity of perspectives in order to have a true debate on the issues surrounding the vote — issues such as the political participation or reduced sentences for the FARC after their demobilization.

In other schools, such as those of the Asociación Alianza Educativa, some teachers have organized debates using the Model United Nations platform to get students thinking as if they were at the negotiating table.

According to Santiago Laverde, subdirector of the Asociación Alianza Educativa, “the classroom has a fundamental role to play in generating opinions on these issues. We need to promote the interest of the youth in their country, their city, and their neighborhood in order to construct a collective conscious and a participative society.”

In general, however, these Bogotano youth are struggling, as are their parents and teachers, to process the information currently available on the peace accords. Although there is a significant amount of information available, much of it is difficult to parse through, especially for youth.

Moreover, the majority of minors in Bogota have not been intimately affected by the armed conflict between the FARC and the government, and much of what the peace accords intend to address will not affect their local environment.

As a result, youth are forming opinions on the peace accords with the information that they can find and understand, mostly coming to them through informal networks: stories from the rural regions of Bogota that are shown on TV; the myths about the peace process, such as the “salaries” that each FARC member will receive for demobilizing; the robberies, fear, or violence that pervades their local neighborhoods; and what their professors say, who are often themselves struggling to process this historic moment.

According to Roberto Romero, a researcher at Bogota’s Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, “The new generation needs resources, as soon as possible, to understand what happened in this country and the sources of the conflicts…We are still lacking curricula that cover themes of peace and reconciliation in this country.”

Although there are laudable efforts by professors to provide educational opportunities and information for youth, the opinions and voices of those under 18 years old are rarely projected beyond the classroom.

The content of youth’s discussions, however, demonstrates that they have highly nuanced viewpoints, that they are not all in agreement with the peace process, and that they know the issues surrounding the accords are not easily grasped.

Whether one travels to public high schools in areas with a high concentration of drugs and gang activity, or to the private schools with landscaped campuses in the north of the city, it becomes clear that youth have carefully-formed opinions, ideas, and attitudes about the peace process, understanding that it is going to impact their future Colombia.

And there are many adults in Colombia, such as Roberto Romero, who know that “The role of youth is determinative in the construction of the nation.” The problem is that this voice — and in general the voice of all Colombian youth — has no value in the social and political discourses that dominate the country.

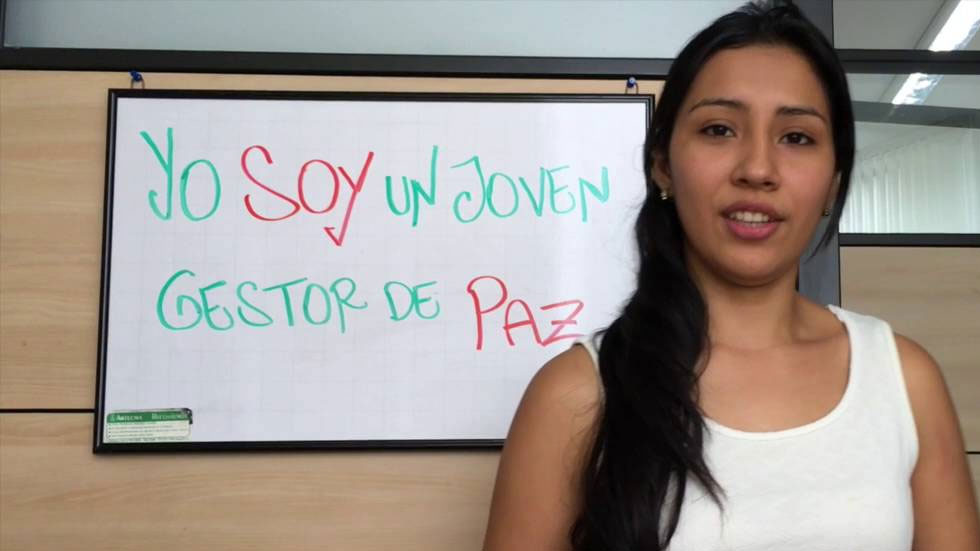

Although there is much talk of the youth, and there exist programs to shape them into “constructors of peace,” these efforts rarely take into account the actual perspectives and thoughts of these students.

Fortunately there are members of civil society truly in dialogue with youth. One example among these is Corporación Vinculos, who have worked to promote understandings of a “subaltern peace” as constructed from the ground up by youth groups in San Rafael, Bogotá. Within the country’s general discourse, however, channels to hear the voices of the future generation are lacking.

“We’ve left the youth behind,” says Santiago Laverde. “We think they don’t have intellectual things to say. [But] they are becoming interested in political issues, and the service of others: issues in their neighborhoods, their communities, and their country.”

This is not to say that the youth are crying out for a right to vote in the plebiscite on the peace process, or that they have any uniform stance on the issues at hand. In contrast, many have recognized that as a group, they lack the appropriate maturity or knowledge of the situation to vote “Yes” or “No.” Moreover, the opinions of Bogotano youth certainly differ from those of Cauca, Chocó, or those who are demobilizing from the FARC.

Nevertheless, as the future generations of this country, youth want their voices to be heard. This could take form, for example, in a simulated plebiscite for youth, in surveys that include minors in their results, and in greater efforts by politicians, teachers, and adults in general to have discussions with youth and to listen to their opinions.

In the end, although today they are younger than 18 years old, they will be the ones leading Colombia towards its long-awaited future of peace and prosperity.

Author Gabriel Velez is a doctoral student in Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago. Author Atticus Ballesteros is a student of anthropology at the the University of Chicago.