Drug trafficking has corrupted Colombia’s armed conflict since the two got entangled in a series of events in 1981 and 1982.

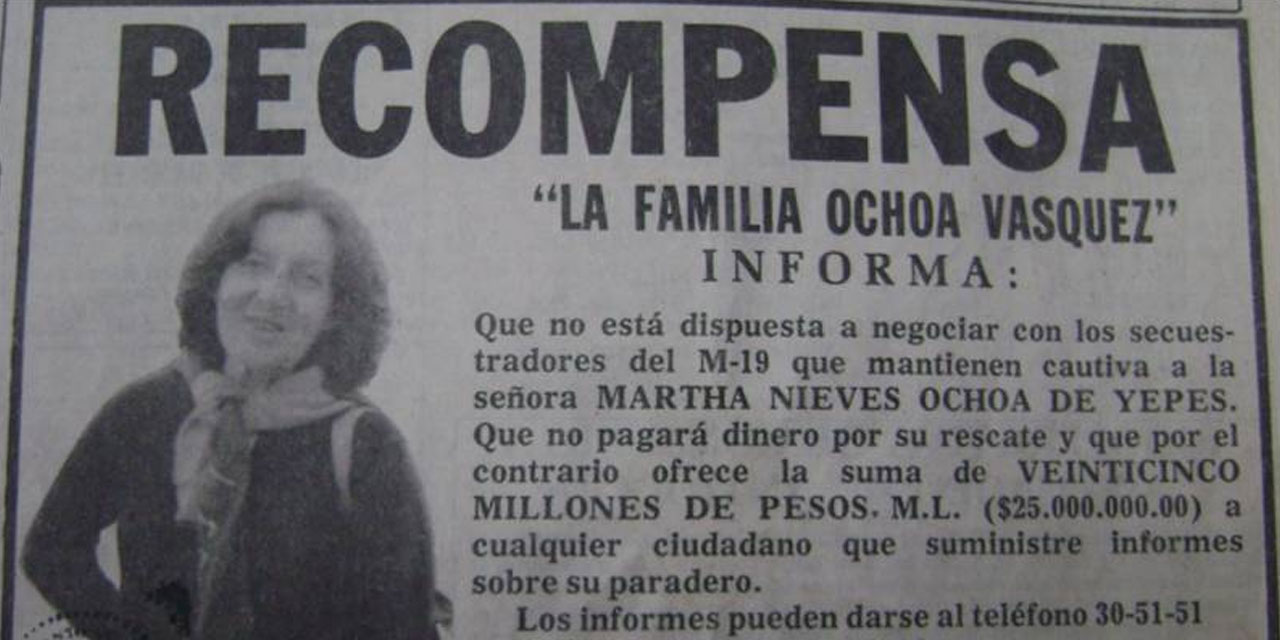

On March 13, 1981, two men dragged Martha Ochoa, the sister of drug trafficking brothers Jorge and Fabio Ochoa, into a car outside a Medellin university.

With that single act, the kidnappers from the left-wing revolutionary M-19 group sparked a chain of events that would change the face of Colombia’s criminal and political alignment for decades to come.

The M-19 guerrilla group was loyal to liberal former dictator Gustavo Rojas.

Wrong family

In response to the kidnapping, drug lord Jorge Ochoa called a meeting of his criminal associates in Medellin.

Each drug kingpin reportedly contributed $7 million to create “Death to Kidnappers” (MAS), a paramilitary group dedicated to ending left-wing kidnappings and extortion.

The organization would receive support from Colombian and American companies, security forces and politicians, setting the standard for later paramilitary groups.

What would later become the Medellin Cartel assembled a well-equipped army of some 2,000 men and launched a brutal killing spree against the M-19.

The drug traffickers’ army did what security forces could not and crushed the left-wing group. Colombia’s Interior Ministry registered 240 political killings by 1983.

“Not only were the M-19 killed brutally, but the brutality was made public… the victims were hung up from trees, they were disemboweled with signs on them to discourage the population from cooperating with them,” testified Ramon Milan Rodriguez before a US Senate committee in the late 1980s.

Medellin Cartel member Pablo Escobar would later become the first to be called a “narco-terrorist.”

Narco-politics

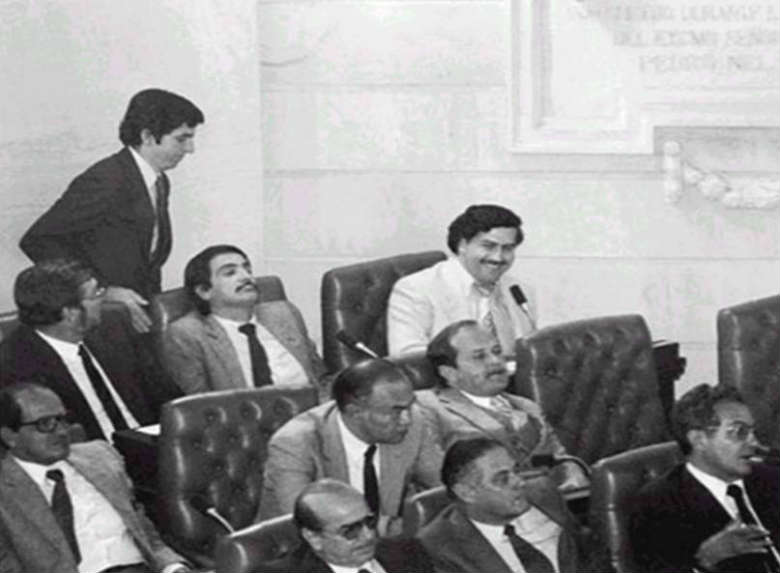

The Medellin branch of the Liberal Party allowed Escobar to take part in the 1982 elections. The drug lord’s image as the “paisa Robin Hood” got him a seat in the House of Representatives.

Pablo Escobar tricks his way into Congress in 1982 on a Liberal Party ticket.

A close friend of the Ochoa family, Liberal Party politician Alvaro Uribe, was appointed Mayor of Medellin in 1982. Other state officials would be given the choice between silver or lead.

In the few months in office, Uribe publicly supported two public works projects financed by Escobar, who had joined Uribe’s Liberal Party in a successful attempt to enter Congress in the same year.

Uribe’s father, a close friend of family patriarch Fabio Ochoa, was killed by FARC guerrillas allegedly because he refused to pay guerrilla taxes.

What united us was not the drug trade, but the horses. When I was a child, horse riding in Antioquia was a source of pride. It had none of the connotations it later acquired. My dad and Fabio Ochoa were friends and rivals in that environment. My brothers and I participated in all the equine fairs, competing against their children in the 60s and 70s.

Alvaro Uribe

Narco-guerrillas

These guerrilla taxes had seen the light at the “7th National Conference of FARC-EP,” held in May 1982 in Uribe in the Meta province.

During this clandestine conference, FARC members agreed that the organization would target the “mass labor” of coca growers to boost the coffers of its revolutionary cause.

Mass labor with coca growers must be done to win them for the revolution, and for this a balance must be maintained between coca production and the cultivation of the family economy, so that it does not degenerate into the constitution of counterrevolutionary bands or of another nature.

FARC

The FARC and drug trafficking: The evidence so far

The system of “taxes” targeted every level of cocaine production and trafficking in areas under FARC control.

Like the M-19, the FARC quickly negotiated a steady income with the drug traffickers that would fund its bloody war against the state.

The FARC’s influence in the drug trade prompted Colombian ambassador Lewis Tambs to accuse the them of being “narco-guerrillas,” a title that would last until 2016.

Armed conflict

While the initial motivation to take up arms originated out of social and political discontent, the emergence of large scale drug trafficking stimulated the country’s armed conflict.

Like the guerrillas, anti-communist paramilitary groups inspired by MAS began depending on drug trafficking, particularly after the death of Escobar in 1993.

This fueled record victimization and corruption that would nearly convert Colombia in a failed state at the turn of the century.

The year 1982 could be identified as a point when the dissolving of the difference between politics and crime began.