Investigating Colombia’s former president Alvaro Uribe has been met with extreme violence ever since authorities found evidence of ties between his family and the Medellin Cartel in 1984.

Criminal investigations have been hampered by violence targeting police, journalists, prosecutors and judges alike.

Bribery used by cartel chief Pablo Escobar and his successors further weakened the justice system to the point it is only able to solve 5% of crimes in the country.

While hundreds of honest officials lost their lives, corrupt officials have enjoyed almost full impunity while embarking on successful careers.

Some, like former cartel associate Uribe, are now among the most powerful and feared politicians in Colombia and have become virtually untouchable for the country’s justice system.

A family affair

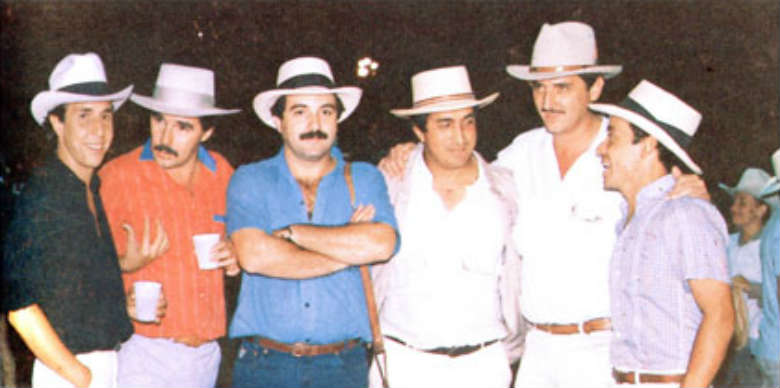

Uribe and his brothers became acquainted with the members of the Medellin Cartel through their father, Alberto Uribe, who was a friend of the Ochoa crime family patriarch Fabio Ochoa.

It wasn’t the drug trade that brought us together, it was horses. When I was a child, horseback riding in Antioquia was a source of pride. It had none of the [narco] connotations it later acquired. My dad and Fabio Ochoa were friends and rivals in that environment. My brothers and I participated in all the horse fairs competing against their children in the 60s and 70s.

Alvaro Uribe

Uribe has always claimed that his father was a cattle ranger and a horse trader, which has been confirmed by Ochoa. Multiple investigative journalists, however, have claimed that the former president’s father was involved in the drug trafficking business of the befriended clan.

The former president’s oldest brother, Jaime Alberto, was so intimate with the cartel that in 1980 he had his first of two children with Dolly Cifuentes, a renowned drug trafficker.

The same year, the 28-year-old Uribe was appointed director of the civil aviation agency, Aerocivil. Escobar had just ordered the assassination of its director, reportedly because of a pending report on the narcos’ growing fleet of aircraft and landing strips.

According to multiple journalists and former cartel members, Uribe granted licenses to many of the aircraft and landing strips used to traffic drugs to the United States and Europe.

Both Antioquia Governor Ivan Duque Escobar —the current president’s father— and President Julio Cesar Turbay were reportedly aware of this, but took no action and left their fellow Liberal Party politician in his post until August 1982.

Two months later, Uribe was appointed mayor of Medellin by Turbay’s successor, Belisario Betancur.

Uribe lasted only 112 days in Medellin’s city hall. According to rumors, he resigned over a meeting with the newly founded Medellin Cartel, but this is disputable.

Colombia Reports verified local press reports from that period and found no indication there was a controversy over ties between Medellin’s city hall and the cartel that effectively controlled Antioquia.

Death of a patriarch

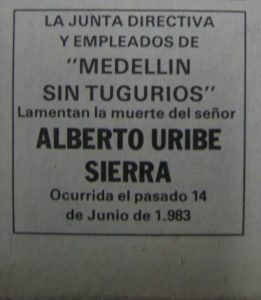

Uribe’s father was killed and his brother Santiago was injured in a firefight on one of the family’s ranches in June 1983, less than half a year after Uribe left Medellin’s city hall.

While Uribe claimed his father was killed in a FARC attempt to kidnap him, this is contradicted by some of the press reports from the period. The FARC has denied any involvement.

The ties between the Uribe family and the Medellin Cartel had become so close that, according to multiple press reports, Escobar lent Uribe one of his helicopters to pick up his brother and the remains of his father. The former president has denied this.

Two months after the death of Uribe’s father, newspaper El Espectador published a report in which it exposed Escobar’s ties to drug trafficking.

By the end of the year, the drug trafficker who was one of Medellin’s most popular politicians became the country’s most wanted criminal and embarked on the most violent offensive against the state in the history of the country.

Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara was assassinated six weeks after seizing a Uribe family helicopter at “Tranquilandia,” a huge Medellin Cartel cocaine processing facility in March 1984.

Colonel Jaime Ramirez, who led the Tranquilandia operation, reportedly told investigators that Lara had warned him that “if they were going to try to kill him it would be the owners of what we seized in Yari.”

“I asked him to explain and he told me: ‘Yes, the owners of the helicopter and the airplanes that were confiscated in Yari’,” Ramirez reportedly said. The colonel was murdered by cartel assassins in 1986.

Many of the cartel’s criminal records were destroyed in November 1985 when M-19 guerrillas and the military fought over control of Colombia’s Palace of Justice in Bogota and the Supreme Court archives were set on fire.

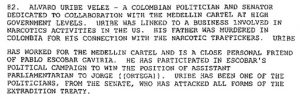

Uribe was elected senator for the first time and entered congress in August 1986, when US Congress was investigating the CIA’s drug trafficking deals with the cartel as part of the so-called “Iran-Contra Affair.”

The director of El Espectador, Guillermo Cano, was assassinated three months later over his newspaper’s persistent investigations into the Medellin Cartel and its associates in Antioquia.

El Espectador’s leading investigative journalist, Fabio Castillo, published the results of his investigations in a book called “The Cocaine Horsemen” in 1987, extensively exposing the Uribe family’s ties to Escobar and the cartel.

Also a native of Antioquia is Senator Alvaro Uribe Velez — whose father Alberto Uribe Sierra was a well-known drug trafficker — who licensed many of the narcos’ pilots when he was director of Aerocivil. Uribe was once detained for extradition, but Jesus Aristizabal Guevara, then Medellin’s secretary of government, succeeded in having him released. The funeral of Uribe Sierra, murdered near his farm in Antioquia, was attended by the then President of the Republic, Belisario Betancur, and a large part of the cream of Antioquian society, amidst veiled protests by those who knew of his links to cocaine.

El Espectador journalist Fabio Castillo (1987)

The pressure from the press, and national and international authorities escalated violence and nearly collapsed the Colombian state.

One by one, Escobar’s cartel associates fell; Carlos Lehder was arrested in 1987 and “El Mexicano” was killed in 1989.

In September 1991, months after the Ochoa brothers and Escobar turned themselves in, Uribe’s ties to them had been picked up by the US Defense Intelligence Agency, which claimed the then-senator was “dedicated to collaboration with the Medellin Cartel,” according to declassified documents.

Escobar was killed in December 1993 and Uribe left the senate half a year later to seek political control of his home province, Antioquia.