Political violence ahead of Colombia’s elections has surged, particularly in regions where some historically have considered democracy a potential threat to their personal interests.

The Electoral Observation Mission (MOE) said in its latest report that it had registered 304 acts of political violence since March 13, the beginning of the electoral year.

This would be a 125% increase compared to the 135 acts of aggression against aspiring politicians, community leaders and rights defenders registered in the same period in 2017.

Social leaders, who generally enjoy popular support over their promotion of a social cause, were the victim of more than half of the aggression followed by politicians and community representatives.

Victims of political violence

Almost half of the 58 political assassinations and more than half of the 41 attempted assassinations since March targeted social leaders, who generally find themselves in opposition against powerful interests as they defend the rights of, for example, ethnic minorities, victims and workers.

The number of assassinations of these leaders increased almost 30% compared to the same period in 2017. Attempted assassinations surged more than 95%.

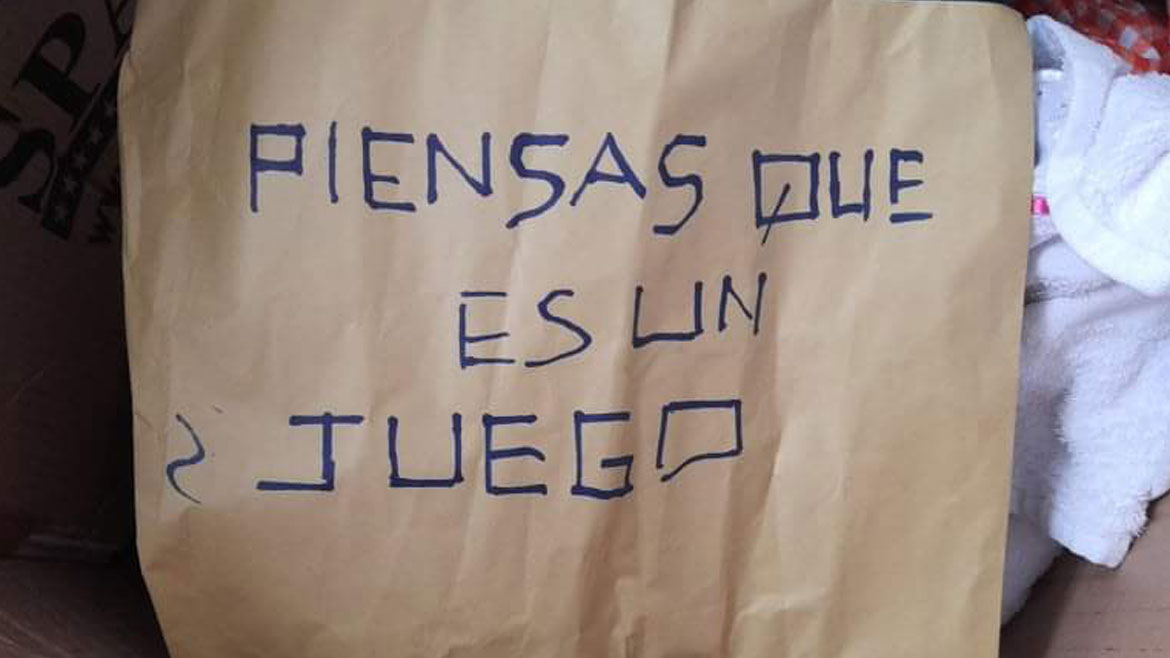

The type of aggression that generated most victims were death threats, which surged a staggering 193%, mainly because of far-right group Aguilas Negras.

Over the past seven months, the MOE registered surges in death threats in the weeks before important electoral events like, for example, the registration of primary candidates.

The electoral observers warned that these threats could end up in deadly violence in the weeks before political parties’ primaries in December.

Nature of the threats

While the majority of politically motivated death threats targeted leaders identified as “leftist” by their aggressors, much of the violence appears to associated with power instead of ideology.

Most of the political leaders who suffered violence were members of the government coalition of President Ivan Duque, for example.

This may indicate that the violence is mainly horizontal, and targets those trying to challenge those in the higher echelons of power rather than those who would be of a different party.

According to a second think tank, Paz y Reconciliacion, the power accumulated by party members of President Ivan Duque’s coalition adds an entirely criminal element to tensions within parties that could turn violent.

According to Paz y Reconciliacion, 90% of the 127 primary candidates with alleged mafia ties are from the government coalition.

These candidates’ aspirations to either grab or maintain power could easily motivate violence without any ideological motive.

Dodgy primary candidates

The oppression in Colombia’s southwest

The violence was most prominent in the southwest of Colombia where there has long been an ethnic conflict between indigenous communities and the descendants of slaves that are disputing the ownership of land of the families of former slave and plantation owners.

Regional distribution of threats

Social violence in this part of Colombia has been a constant for decades and easily becomes political in an election year.

Growing disapproval of Duque’s far-right regime and the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic add to instability as voters of all shapes and sizes have demanded change, causing tensions with those who are happy with how things are.