Medellin’s authorities will demolish Pablo Escobar’s former home, sparking debate about whether the city’s history – and indeed present – is being respected, or simply erased. Many believe the demolition is an empty symbolic act – Escobar only lived in the building for a few years, and it was never the centre of cartel operations.

This is the act of a vain mayor: it’s simplistic. The Monaco Building is a convenient focus – it’s a show.

Journalist and scholar Juan Diego Restrepo

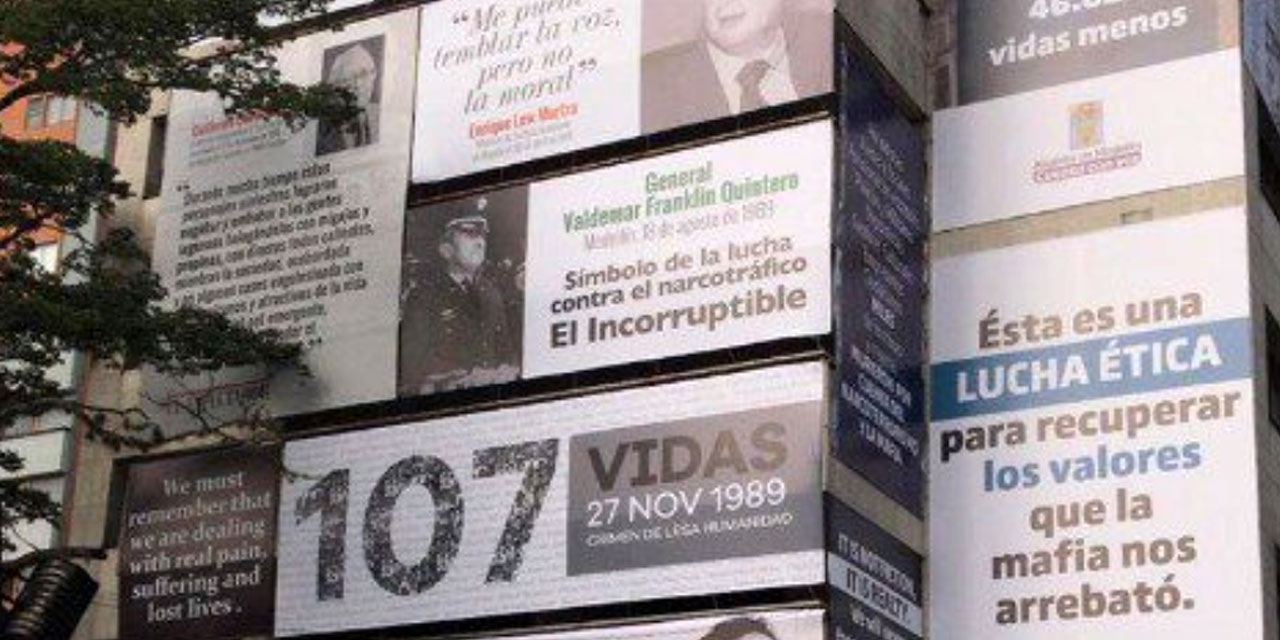

The Mayor has argued that the act is a way of re-appropriating Medellin’s history, of telling the story from the point of view of those who were victims, rather than those who created terror.

It is not a question of hiding the past: quite the opposite. We are returning to the past to tell the story again, but from a perspective which is respectful of its pain.”

Medellin Mayor Federico Gutierrez

One of the major criticisms of the demolition is that violence and mafia criminality are not simply a part of Medellin’s history: they are a part of its present, as well as a heritage which remains largely unaddressed. Some believe that this is an attempt to sanitize the image of the city, to erase the historic links of the city’s living political elite to corruption and criminality.

It is in the interest of Medellin businessmen that reminders of drug trafficking disappear, because their ghosts from the past — who helped them to get ahead in times of crisis with total impunity — disappear with those reminders.”

Journalist and scholar Juan Diego Restrepo

Medellin has tried to portray itself as an example of urban transformation, but registered an increase in homicides for the third consecutive year in 2018 and continues to be Colombia’s drug trafficking capital. More than half of Medellin’s homicides last year were by alleged members of the “Oficina de Envigado,” the organized crime syndicate founded under Escobar that is estimated to have 5,000 members and continues to be tied to the city’s elite.

Another issue raised is that the Monaco Building has become a “straw man”: Escobar was a symptom of what is tormenting Medellin and not a cause. Painting the demolition as a symbolic end of narco-culture in Colombia is disingenuous.

Narco-terrorism was not born of one individual and will not be destroyed with one building: the systematic failures which produced and supported Escobar’s vicious hold on the city persist, from deeply rooted socio-economic deprivation to an entrenched corruption and violence in the political and economic systems. These conditions continue to produce mafias and violence.

The discussion must be ‘de-Escobarized.’ The city suffered the horror of narco-terrorism because of a shameful alliance of mafia, businessmen, and sectors of the Colombian police.

Journalist and scholar Juan Diego Restrepo

The focus on the building seems even more shortsighted in the light of the sheer numbers of individuals and groups complicit in the function of the Medellin Cartel, from football players and businessmen to police elements, as well as a whole neighborhood constructed by the cartel – still named Barrio Escobar.

In response to these criticisms, the Mayor named the project ‘Medellin embraces its history´, though many have criticized the way Medellin’s authorities ’embrace’ the city’s history, activist Monica Betancur said, “The way Medellin ’embraces’ its history is indifferent, exclusive, and without justice for victims.”

With this destruction, the mayor has adopted the same tactics as the cartel, he is blowing up the building of a man who tried to blow up our city. We should be doing things another way.”

Juan Diego Restrepo

Quite aside from intellectual discussions of history and memory, the Mayor claims that the building needed to be destroyed for more practical reasons: “The economic argument is not the most important one, but it is worth mentioning that renovating that building would have cost ten times more than demolishing it and then building a physical space dedicated to memory.”