Colombia’s anti-government protests have shown that the country’s youth no longer accept living in a country that has oppressed them for decades.

The latest protests seem to be the final stages of a decades-long struggle between young people demanding opportunities and authorities demanding conformity.

The origin of the protests that have President Ivan Duque against the wall can be traced back to 2011 when students successfully sunk former President Juan Manuel Santos’ education reform plans.

Until that year, organizing student protests was almost impossible due to the fierce persecution of anything deemed “subversive” by now-defunct paramilitary group AUC and former President Alvaro Uribe, the informal boss of the current president.

According to a recent student by the Gran Politecnica university, more than 10,000 were detained mainly on rebellion and terrorism charges between 2000 and early 2018.

Only 491 of these students were found guilty as most arrested students were the victim of a systematic campaign to criminalize activism, particularly during when former President Alvaro Uribe was president between 2002 and 2010.

The systematic criminalization of Colombia’s youth | 2000 – 2018

The 2011 blow

The end of the Uribe administration and the dismantling of intelligence agency DAS ended much of the persecution, which allowed student protests to successfully sink a government policy proposal in 2011.

Santos withdrew his education reform proposal that sought a partial privatization of Colombia’s public education system in November that year after more than six months of protests.

The success allowed the students to play a major role in 2013 protests against an agricultural reform in which they supported a farmers’ uprising.

The increasingly organized students remained a voice to be reckoned with, which was completely underestimated by President Ivan Duque after taking office in 2018.

The students took to the streets almost immediately after the president took office and wanted to meddle with education budget and forced Duque to withdraw his proposal.

Colombia’s students ignore Duque and maintain strike to demand education funds

The prelude to the current protests

(Image: Sergio Fernandez)

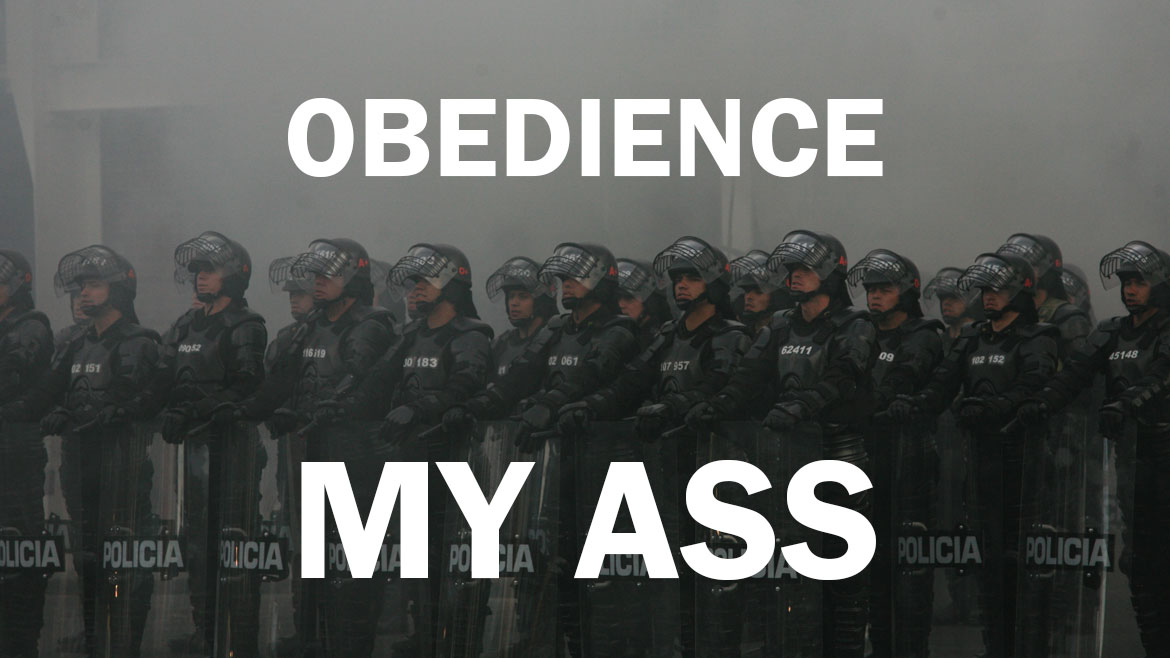

Bogota students took to the streets again in September 2019 in protests against corruption, but were brutally repressed by the ESMAD after police infiltrators engaged in vandalism.

In response, students across Colombia rose up to demand the dismantling of the loathed riot police unit on top of measures to curb corruption and government compliance with agreements that ended the 2018 protests.

Teachers joined the students in October that year and indigenous groups, farmers and labor unions joined to call for a national strike in opposition to a tax reform in November 2019.

First national strike

The national strike triggered the largest anti-government protests in more than four decades despite attempts to criminalize the protests.

The police escalated its violent crackdown, which only grew support for the protests led by the students exactly like before.

This time, the violence tanked the approval rating of Duque and triggered a lawsuit that sought to restrict police brutality.

Anti-government protest in Medellin (Image: Jorge Calle)

The National Strike Committee that was formed to organize the protests called for a Christmas break in December and a resumption of protests in early 2020 to force the government to negotiate their demands.

The coronavirus forced the strike leaders to suspend their protests, but in September received the support of the Supreme Court, which ordered the government to end the violent repression of protests.

The latest round

Duque proposed another tax reform in April this year, which triggered the National Strike Committee to call for another strike.

The April 28 strike wasn’t nearly as successful as the one in November 2019, but found an unexpected ally in the president and his new Defense Minister Diego Molano.

The defense minister should have remembers how the violent crackdown of the September 2018 and November 2019 protests only made them bigger, but Molano apparently is an idiot.

The defense minister called in both the National Police and the National Army to quell the protests even more brutally than before, triggering an even bigger backlash.

While Molano was virtually begging the Supreme Court to throw him in prison, the protests swelled to proportions similar to those in 2019 and the government received international condemnation.

As if the defense minister wasn’t in enough trouble with the Supreme Court already, the opposition filed criminal charges before the International Criminal Court.

Within days, Congress withdrew its support for the tax reform and Finance Minister Alberto Carrasquilla resigned.

After US lawmakers demanded the suspension of military aid to Colombia’s police, Foreign Minister Claudia Blum also resigned.

Uribe dropped Duque like a disposable puppet, bringing the government on the brink of collapse.

Ten years after their first political success, Colombia’s youth showed the country they can no longer be beaten into submission, but can seal presidents’ political death.