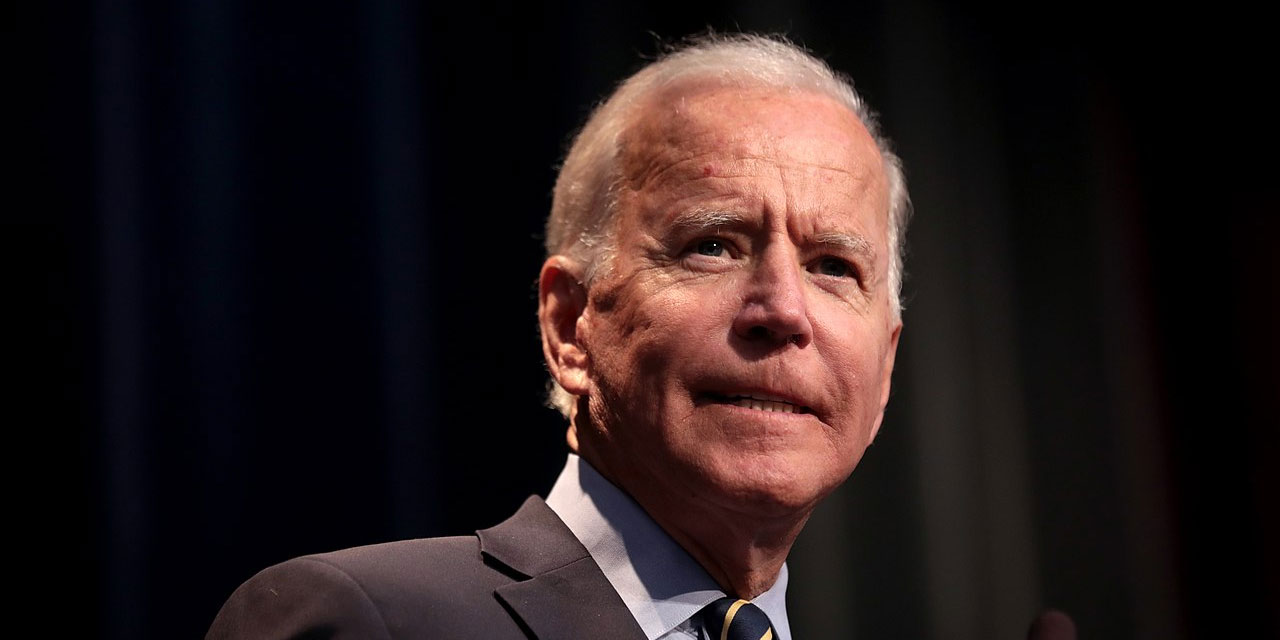

One of US President-elect Joe Biden’s virtues is a willingness to acknowledge mistakes, which may come in handy as he’s made some catastrophic ones in regard to Colombia.

Now, as Biden begins to craft his own foreign policy, will he again be open to changing his mind? US policy with Colombia is one area desperately needing a reboot, and it’s up to Biden to lead that.

Every October for the past twenty-five years, each US president has declared a “national emergency” because “the actions of significant narcotics traffickers centered in Colombia continue to threaten the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.”

Bill Clinton signed the first Executive Order #12978 in 1995. Donald Trump issued the most recent one three weeks ago, Oct. 19, 2020, re-affirming that “narcotics traffickers centered in Colombia” continue to cause an “extreme level of violence, corruption, and harm in the United States and abroad.”

In October 2021, will President Joe Biden follow the lead of Presidents Clinton, Bush, Obama and Trump? Will he sign the same annual confession that US policy for Colombia has not achieved its goals?

During the past quarter-century of unending “national emergency,” the US sent $12 billion in aid to Colombia, including $573 million in fiscal 2020. Isn’t it time to say there is a basic flaw in US policy? How else does one explain failure to resolve the emergency?

The failings are laid out very clearly even in US government reports, as shown below.

Since 2000, US policy has gone under the name ‘Plan Colombia,’ as it was labeled in a billion dollar appropriation that first year. Most of the first round’s funding bought helicopters to give to Colombia’s army and national police.

While a Senator, Biden helped create and sustain Plan Colombia, as chairman (and ranking member) of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The fear today is that as president, his Colombia policy will fail to break with the past.

Biden himself implied that less than a month before the election, writing an op-ed for newspapers in Orlando and Bogota he hoped would woo Florida’s Colombian-American voters. He wrote:

“I championed Plan Colombia from the very beginning and secured bipartisan support for its passage through Congress…It is one of the most successful—and bipartisan—foreign policy undertakings of the last half century.”

Bipartisan, yes. Successful? Twenty-five years of national emergency suggest not quite.

Plan Colombia was controversial in Congress in 2000 and in subsequent funding cycles. Critics said—correctly—it was too focused on military activity and not enough on social and economic programs and human rights.

“Some 80% of the aid in Plan Colombia comes in the form of military weapons,” said Rep. Cynthia McKinney (D-Ga.) in September 2000. “So, although Plan Colombia was originally intended by [Colombian] President Pastrana to be a multinational aid package, it has now morphed into a US military operation.”

As McKinney noted, from the beginning Plan Colombia failed to attract international support because of its heavy-handed approach to social and economic problems.

A cable in May 2004 from the US Embassy in Colombia to State Department headquarters makes clear that regarding Colombia, the US was odd man out in international circles. In a meeting in Bogota with seven European, Asian and North American allies of the US and Colombia, a United Nations delegate explained that “alternative development, rather than law enforcement, should be the first response in many areas where illicit crops are grown.”

But the militarists won the Congressional debates in 2000 and every year since. US policy has continually stressed building Colombia’s security apparatus, with social and economic programming pushed to the sides. It’s time to reverse the priorities.

Plan Colombia’s original goals were lofty. The 2000 law that launched it stated its purposes were “to combat drug production and trafficking, foster peace, increase the rule of law, improve human rights, expand economic development, and institute justice reform.”

Regarding drug production, Plan Colombia has been an obvious, unambiguous, notorious and deadly failure.

Today, 50% more Colombian land is devoted to growing coca than in 2000. The most recent US National Drug Threat Assessment, published by the Justice Department in December 2019, reported: “Coca cultivation and cocaine production in Colombia, the primary source of supply for cocaine in the United States, remain at high levels.”

The report added, ominously: “High levels of coca cultivation and cocaine production in Colombia are likely to persist. Due to the ongoing proliferation of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids into the expanded domestic cocaine supply, cocaine-involved deaths will continue to rise for the near future, with the potential to reach epidemic levels previously only associated with opioids in the next few years.”

But cocaine is only the most glaring of Plan Colombia’s failings. Serious problems have been an open secret within the US government for years, as noted in scores of reports from US government agencies such as the State Department, Justice Department, Government Accountability Office and Congressional Research Service.

The 2020 Human Rights Report from the US State Department summarizes just some of the failures in Colombia: “The Government’s human rights record remained poor…Government security forces continued to commit serious abuses, including extrajudicial killings…Members of the security forces collaborated with paramilitary groups that committed abuses…Government corruption was a serious problem…Groups continued to lay land mines…Illegal armed groups committed numerous political and unlawful killings.”

Nevertheless, Plan Colombia did have one spectacular success: arming, training and guiding Colombia’s security forces into becoming the US’ No. 1 military ally in Latin America.

The Colombian and US Army, Navy and Air Force conduct joint operations ranging from aerial jet refueling to submarine reconnaissance. Colombian soldiers, acting as proxies for US troops, have trained security forces in over 70 countries. Colombia’s military is a reliable bulwark for the US on Venezuela’s western border. At the moment, about 50 US Army soldiers, part of the Army’s 1 st Security Force Assistance Brigade, are stationed in Colombia, despite intense recent controversy and legal action by Colombian opposition legislators.

Of course there is an alternative approach, one US policy-makers knew about—and rejected—from the beginning. It’s a policy with human rights and economic development at the core, not the peripheries.

It’s what the UN and European experts–as noted above–were telling the US Embassy in Bogota in 2004: “Alternative development, rather than law enforcement.”

What would it look like? There are people in the US Agency for International Development who know what could be done. There are lots more within the US and Colombian governments, international agencies and the global NGO network.

Will Biden’s foreign policy strategy embrace a human-centered policy for Colombia? Or will it remain stuck in military mode?

Obama and former Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos each took baby steps in the right direction. Obama by proclaiming “Peace Colombia” to replace Plan Colombia, Santos by challenging the ‘war on drugs’ mentality. There are politicians from whom Biden can take a cue.

Come October 2021, Biden must choose whether to sign the twenty-sixth consecutive Executive Order #12978 declaring a national emergency regarding Colombia’s drug traffickers. For the sake of both countries, he needs a new script.