The Colombian government’s delay in submitting a crucial tax reform to tackle a plunge in oil revenue and a tricky overseas scenario could prompt a cut in its credit rating this year, boosting the cost of its debt and moving it closer to speculative grade, investors fear.

While Colombia’s problems are far less severe than those of Brazil, which lost investment grade in 2015 and is tackling recession, the nosedive in oil and coal revenue has deteriorated Colombia’s fiscal accounts, limited wiggle room and forced it to raise funds elsewhere.

Even so, the government distressed some investors last week with its announcement that a long-awaited structural tax reform to raise additional revenue would no longer be sent to Congress for debate in the first half.

The government said it wants more time to sell the idea, but market speculation links it to President Juan Manuel Santos’ desire to sign a peace accord with Marxist rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) before any unpopular fiscal measures are taken.

“It’s very important that they get a tax reform done this year since the fiscal balances have deteriorated quite a lot,” said Lars Peter Nielsen, senior portfolio manager at Global Evolution in Denmark, which holds peso-denominated debt.

“I’m a bit worried that the rating agencies will not give them more room if they continue to postpone the tax reform and we could see a downgrade or at least a negative outlook later in the year.”

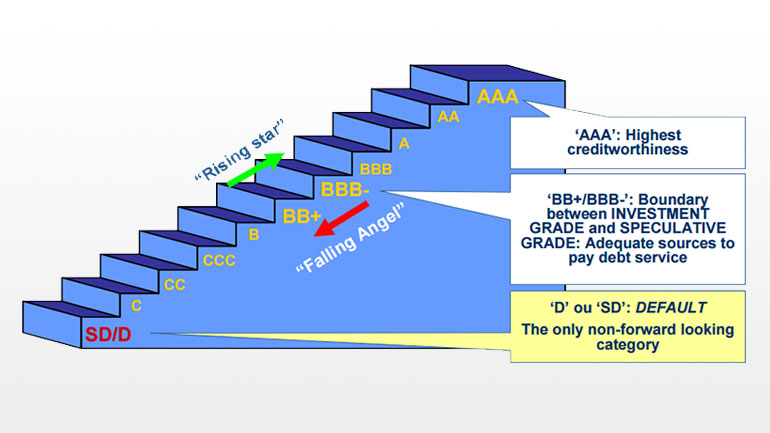

Colombia is rated one notch above investment grade – which it won in 2011 – with stable outlook, by Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s.

The tax postponement was accompanied by a reduction in the estimated average oil price used in this year’s financing plan to $34.7 per barrel from $50 originally. That would result in a wider fiscal deficit than the government’s target of 3.6 percent of the gross domestic product.

Colombia’s peso currency has dropped almost 40 percent over the last 12 months as global oil prices plunge, lower U.S. interest rates attract cash away from Colombia, and uncertainty in China pushes investors toward safer havens.

Although Finance Minister Mauricio Cardenas has emphasized that spending cuts will reduce the shortfall, rating agencies have reiterated the importance of increasing revenue.

Lisa Schineller, a sovereign ratings analyst at S&P, said the government has “a track record of adjusting on both expenditure and revenue; we’re assuming that track record holds going forward.”

“If the pace of adjustments is not in line with what we are expecting then certainly we could act,” she told Reuters.

Reflecting market uncertainty, insurance against a Colombian default – known as credit default swaps – last week touched 358 points for 10-year global bonds, its highest level since April 2009.

The spread between Colombian dollar bonds and comparable U.S. Treasuries has nearly doubled in the last year to 401 points on the EMBI index, higher than countries including Peru, with 277, and Mexico with 267.

“Overall, I think confidence in the nation is fragile, it could break at any time if necessary measures are not taken. There’s a lot of concern,” said Mario Castro, strategist at Nomura Securities in New York.

“It would not surprise me to see a negative outlook in the second half because of the delays … and that would mean Colombian assets will continue to lag behind its peers.”

Another vulnerability that plays against the nation’s rating is the current account balance of payments deficit, which in September stood at 6.6 percent of GDP, equivalent to $14.5 billion. That is “unsustainable” according to Cardenas.

(Editing by Matthew Lewis and W Simon)